Despite the nonsense that pervades the mainstream media… renewable energy isn’t saving the planet anytime soon.

If you believe it will, I have a bridge to sell you in Brooklyn.

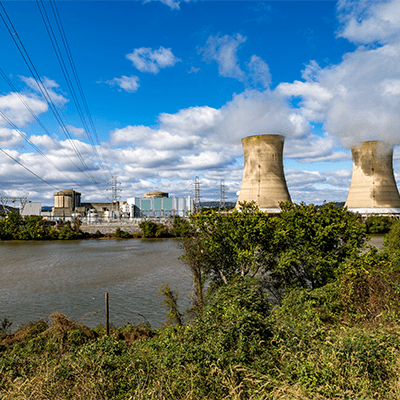

Today I break down why renewables are overhyped… and why nuclear power is the answer when it comes to saving the planet.

Ep. 75: What to save the planet? Use nuclear power

The Mike Alkin Show | 75

Want to save the planet? Use nuclear power

Announcer: Free and Clear, the chatter from Wall Street. You’re listening to Talking Stocks Over Beer hosted by hedge fund veteran and newsletter writer, Mike Alkin, who helps ordinary investors level the playing field against the pros by bringing you market insights and interviews with corporate executives and institutional investors. Mike sifts through all the noise of mainstream financial media and Wall Street to help you focus on what really matters in the markets. Now, here is your host, Mike Alkin.

Mike Alkin: It’s Monday, October 7, 2019. Hope you had a good weekend. I had a nice weekend. Starting to get some fall weather here in New York, although, this morning, I go outside to take the kids to school, and it’s in the 70s, so not quite what I wanted. Saturday night, I was at my son’s lacrosse game, and wearing a hat, had some gloves on. It was in the 40s. It was perfect. Got a little lucky, and here I am. You talk about you’re never satisfied weather-wise. I’m always looking forward to the next season. I guess that’s when you live in a climate that has four solid seasons, you have to adapt.

Mike Alkin: One of the dads was … We were laughing in the stand because it was like high 40s, and he was playing in a field that was right by the Long Island Sound. When the winds are kicking up there, it could be brutal. Here it was, it was 47 maybe degrees, and the wind was just starting to come in off the sound a little bit. We were joking because we were saying, or the dad said, “Here, look at all of us. We’re sitting here freezing, yet if this were April, we’d be excited, and we’d probably be in t-shirts because we’re coming off of a tough winter.”

Mike Alkin: So, it’s good to get the chill back in the air. Pretty excited about that. I don’t think I mentioned it last time, or maybe I did, but I don’t think I did. A couple of weeks ago, I was cleaning my grill, and I bent down just to get the scraper, and I threw my back out. I literally felt like somebody shot me. It was agonizing, and I thought, “Oh, you’ve got to be kidding me.” Whatever day it was, I couldn’t really move for a day or so, and it was ridiculous.

Mike Alkin: Then, my daughter said, “Dad, you should try the acupuncturist.” She has an autoimmune disease, and part of that is a side effect is rheumatoid arthritis that she has. Sometimes, it gets to her. She uses an acupuncturist, and it does wonders for her. So, I went. I said, “Okay, let me try it,” and I went, and in less than a week, in three sessions, it’s brand new. I couldn’t move. Trying to get out of bed in the middle of the night to go to the bathroom, it was ridiculous.

Mike Alkin: My wife was laughing because try to see me roll out of bed and get there. Not laughing, just saying, “Look at you. You’re an old man. What’s wrong?” I have to say, I don’t know what people’s views are on it, but, for me, I have to tell you, it was game-changing. So, I’m pretty excited about that. Now, I’m back.

Mike Alkin: I just got a Peloton. We ordered a Peloton for the house, the bike, and it’s been great. I don’t know. Actually, the stock just came public, and I don’t have an opinion on it except I spent a lot of money to not earn a lot of money, but hopefully, eventually they get there, I guess, for them, for shareholders, I don’t really care on it.

Mike Alkin: But I have to say, it’s pretty interesting. It’s an interesting concept. My daughter and my wife go to SoulCycle, which is packed all the time. What a business that is. It’s spinning class basically, but they go, and they pay their 35 bucks each time. Every time I turn around, my daughter’s at SoulCycle and my wife. We bought a Peloton to have in the house, and pretty cool. You got a great screen. You have a choice of, I think it’s 12,000 rides you can do with different instructors. I don’t know how many they have, maybe 12, 15. You can do live classes online, but you have a nice tablet on the bike in front of you. It’s connected.

Mike Alkin: So, you can take live classes or the library, I think it is 12,000, and all different rides. You can filter it by genre of music. You can filter it by time, by the type of workout you want. What’s pretty cool, because I had a spin bike, but it was an old spin bike, but you could see … You never knew. Am I going fast? Am I going slow? You could figure that out, but you really don’t have your cadence. You don’t know what your output is. You don’t know really any sense of how many calories you’re burning, how far you’ve gone.

Mike Alkin: On this bike, on the screen, it tells you everything. It’s a great motivator. On the right side of the screen, it shows you all the people who are either in the live class or have taken it all time. There’s a lobby, so you can see who’s in that lobby. Then, you could compare it, and you could see. So, it’s kind of motivating because you could move up. People use screen names like they do on Twitter, so you have no idea really who most people are, but you could see, “Okay, what’s my output, and gosh, if I could just move a little bit faster.”

Mike Alkin: I have to tell you after 45 minutes … It’s 45 minutes to an hour, depending on which you do, but you’re drenched. It’s a 45-minute, one-hour workout that you burn, five, six, 650 calories, and really spent. I can feel it in the cool down. Just getting done and doing whatever, it’s a good 30 minutes by the time your body starts getting back. You could actually feel it throughout the rest of the day. You can kind of feel you’re still pumped up.

Mike Alkin: I’m pretty impressed. Customer service was great. It was a great experience. They came. They delivered it. They were here in 20 minutes. They did what they had to do, really polite people, very courteous when they called to say they were coming. They were there when they said they would be there. Again, I don’t own the stock. I haven’t researched the stock, but I was very excited about the experience, so for whatever that’s worth.

Mike Alkin: I’m not going to have a guest this weekend because I got to thinking. There’s an investor in the fund that I run. A smart guy and always trying to come up with ideas, and has a friend of his who is not an investor, but emails me once in a while and is trying to learn about the nuclear power space. That’s what I focus on. I’ve spent years now researching the renewables, the alternatives to nuclear power, the safety of nuclear power, the waste stream because people are worried about the waste, and long before I ever decided to express that view in a vehicle got very comfortable with that.

Mike Alkin: What happens though, and you see it on Twitter, you see it in other places, people will want to question that and ask questions about it. After years of doing it now and staying on top of it every day and understanding the role, you sometimes a little exhausting, but for people who are learning it, it’s all-new. So, I like to always hear them. Maybe they’ve got some insights that I don’t have, and, certainly, I don’t have a lock on the insights on that. So, I’m always wide open to it.

Mike Alkin: This one guy was emailing me this weekend and last week with a lot of questions and opinions. Had more opinion than fact, way more opinion than fact. I was tolerant for a while of that. I tend to not be too tolerant when arguments are not fact-based, so I tend to be a little bit more forceful in my views and my time with people who are more driven by either a singular view or not backed by great research. Hey, what are you going to do? Sometimes you give a courtesy to people.

Mike Alkin: It got me to thinking. One of the people when I was researching and doing a lot of work for a long time and I still follow and I’ve had as a guest is Mike Shellenberger. Mike grew up, I think, in a passivist family, I think a Mennonite family, and grew up always camping and doing all sorts of stuff. He grew up to be a real environmentalist, very pro-wind, pro-solar, pro-renewables. He wound up really making that his life’s vocation and was instrumental in getting this renewable movement under the Obama administration. I think he said at one point they spent $150 billion over a several-year period.

Mike Alkin: He did that, then all of a sudden, over time, he started to become disillusioned with it, with the promise of renewables, and he started to look at … I should say Mike Shellenberger is a time hero of the environment. He is with the Environmental Progress. He’s the founder and the president of Environmental Progress, but Mike did a lot of work. Smart guy, and he eventually became a real supporter and activist for nuclear power, so he switched sides if you will. He’s still for clean air, but he switched sides.

Mike Alkin: He started doing his research, and he’s become very vocal, and he’s a big believer. His view is, “Hey, renewables can’t save the planet.” As I was going back and forth in emails with this fellow, I revisited some of Mike’s work after I … Because what I really wanted to say, “Just read this because this is what I think because I’ve done a lot of research on it. This is my view, and here. It’s a weekend. Leave me alone. I’ve got kid stuff to do.”

Mike Alkin: Anyway, it was interesting, and Mike has a really good piece out there, which is … If you haven’t read it, I would really go to the website Environmental Progress, and you’ll see some of his recent writings. It doesn’t form my opinion, but the research that went into it and … I think he wrote this sometime this year, but a couple years ago, you could piece it all together. I just didn’t write a public piece on it, but this kind of summarizes about it, my views on it. I think, for those people who are trying to explore what’s their view, trying to form a view, renewables versus nuclear versus fossil fuels.

Mike Alkin: Last week, I had Don Watkins on who edited the book, The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels. I’m trying to bring some different aspects to this stuff. I would recommend reading that, but I’m going to kind of summarize for you here because I think it’s kind of worth going over it. Mike talks about the renewable case and why. He says, “Look, it just can’t save the planet.” He goes into solar, and he says, “Electricity from solar roofs cost about twice as much as they do from solar farms, but solar and wind farms require huge amounts of land.”

Mike Alkin: He goes on, and he talks about the fact that solar and wind farms require long, new transmission lines. Interestingly, those are opposed by local communities and conservationists who are trying to preserve the wildlife, particularly birds. You really think about it, the challenge is the intermittency nature of solar and wind. If you’ve done even a modicum of research, you’ve heard the old saying when the sun stops shining and the wind stops blowing, you have to be able to ramp up another source of energy. Without a large scale way to back up solar energy …

Mike Alkin: Use California for an example. They’ve had to block electricity coming from solar farms when it’s really sunny. They’ve even gone so far as to pay neighboring states to take it from them so they can avoid blowing out the grid. One of the things we’ll talk about, as you’ve heard, this battery revolution that’s coming down the pike, and there’s many reasons that that’s not the case. Battery storage, if you will, but not on grid-scale, and I talk about that in a little bit. There’s both technical and economic reasons why that’s not likely.

Mike Alkin: One of the things that you see is it does have a big environmental impact. Hawks, eagles, owls, condors, the wind turbines just eat them up. They didn’t evolve. They evolved and learned how to survive, but they didn’t evolve and learn how to survive with giant, several hundred-foot, massive wind turbines spinning through the air. In some cases, wind turbines are really the most serious threat to a lot of bird species. Same thing with solar farms, they also have a big ecological impact. The land usage is pretty staggering, and we’ll talk a little bit more about that in a bit.

Mike Alkin: As you think about this, but there’s some real just fundamental problems with the renewable energy business. You can make solar panels cheaper. You can make wind turbines bigger, but at the end of the day, you can’t make the sunshine more regularly, or you can’t make the wind blow more reliably, and, as Mike points out, the environmental implications of the physics of energy. If you’re going to produce huge amounts of electricity from weak energy flows, you have to spread them over enormous areas. One of the problems with the renewables is it’s not necessarily fundamentally technical. It’s natural. You’re dealing with unreliable energy sources that require huge amounts of land that come at a massive economic cost.

Mike Alkin: I know you read the papers. Listen to me. I sound dated. You listen to a podcast. You listen to TV. You read a website, and there’s all this talk about how solar panels and wind turbines have come down in costs. It’s true. You’ve got these massive, one-time cost savings because they’re made in these big Chinese factories. The real issue, though, is that’s a one-time cost saving. It doesn’t solve the unreliability factor of what they are, the intermittency.

Mike Alkin: If you think about California between 2011 and 2017, the cost of solar panels declined 75%. Yet, electricity prices rose five times more than they did in the rest of the United States. Same thing in Germany, they’re the world leader in solar and wind. Between 2006 and 17, their electricity prices increased 50% as it spent, I think, I don’t know, six, $700 billion on renewables. Their carbon emissions since then, say, well, since ’09, Germany’s carbon emissions have been flat despite this mass of hundreds of billions of dollars investment into its electricity grid, so flat CO2 emissions and a 50% rise in the cost of electricity.

Mike Alkin: France produces a 10th of the carbon emissions per unit of electricity as Germany, and they pay a little more than half of the electricity costs. Well, 75% of their grid is nuclear power. Then France went on … From their neighbor, Germany, they were feeling pressured, and they spent almost $35 billion on renewables in the last 10 years. What happened? A rise in the carbon intensity of its electricity supply and electricity prices went up. They had originally planned to wean off of nuclear from 75%, down to 50% by 2025, and they came out in the last year and said, we can’t do that. It’s got to be by at least 2035.

Mike Alkin: Then you hear all the talk about how expensive nuclear is compared to cheap solar and wind, but those are headline numbers. The fact is 70 to 80% of the cost of a nuclear power plants are upfront. They’re several billion dollars. What you don’t see in those numbers is the cost given for solar and wind that include the high cost of the transmission lines, the new dams, or other forms of battery, battery storage.

Mike Alkin: You come to the part, well, which I hear all the time, “Yeah, but nuclear power, is it safe? What about all that waste?” That’s the most common thing I’ll hear, nuclear waste. As Mike points out, every major study since the 1960s, including a recent one by the British medical journal, Lancet, concludes the same thing. Nuclear is the safest way to make reliable electricity. He brings up the point. He says nuclear power plants are so safe for the same reason nuclear weapons are so dangerous. The uranium used as fuel in power plants and as a material for bombs can create one million times more heat per its mass than its fossil fuel and gunpowder equivalents.

Mike Alkin: Because nuclear power plants produce heat without fire, they emit no air pollution in the form of smoke. The smoke from burning fossil fuels and biomass results in the premature deaths of seven million people per year, according to the WHO. Again, if we were to ask Don Watkins from The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels, he write … What’s his view? He would say, “Well, by burning those fossil fuels, how many billions of people have we brought into a better standard of living?” So, there’s a whole debate around that.

Mike Alkin: It all comes down to math. You always hear me say, “It’s fourth-grade math.” I say that all the time when it comes to the case for uranium mining and nuclear power and where we are in the cycle. Everything for me comes out in fourth-grade math. If you could add, subtract, multiply, and divide and just do the work, you can uncover a lot of truths. “Even during the worst accidents, nuclear power plants, really small amounts of radioactive particulate from the tiny quantities of uranium atoms split apart to make heat,” Mike says, and I agree. Over an 80-year lifespan, fewer than 200 people will die from the radiation from the worst nuclear accident, Chernobyl, and zero will die from small amounts of particulate matter that escaped from Fukushima.

Mike Alkin: James Hansen, who was a noted environmentalist turned pro-nuclear guy, along with Shellenberger, have studied that they think nuclear plants have saved two million lives that would have been lost to air pollution. When you think about the land density, the energy density of nuclear, in California, a solar farm requires 450 times more land to produce the same amount of energy as a nuclear plant. Because it’s so energy-dense, nuclear requires far less in the way of materials and produce far less in the way of waste compared to energy-dilute solar and wind. “A single coke can’s worth of uranium will provide all the energy,” as Mike says, I laugh, “even the most gluttonous American or Australian lifestyle would require.”

Mike Alkin: That’s fair. You can pick on the Americans. The high-level radioactive waste that nuclear plants produce is the very same coke can of used uranium fuel. Mike points out that the reason nuclear is the best energy from an environmental perspective is because it produces so little waste, and none enters the environment as pollution. If you were to take all of the fuel over the last 45 years of the Swiss nuclear program in canisters, the waste, it’s the size of a basketball court where all the spent nuclear fuel is. Solar panels require 17 times more materials in the form of cement, glass, concrete, steel than do nuclear plants, and they create 200 times more waste.

Mike Alkin: Now, you tend to think of solar panels as clean, but the reality is there’s no plan anywhere to deal with the solar panels when they come to the end of their 20 to 25-year lifespan. Nuclear power, you’ve got 40-year plants that get extended to 60 and 80-year plants. The waste is contained on-site in concrete, reinforced casks. Solar panels will last you 20 to 25 years. There’s no plan for the waste, so what’s going to happen? They’re shipped along with other forms of electronic waste to be disassembled, smashed by hammers. And where does that go? It goes in poor communities in Africa. It goes to Asia. All those residents are exposed to the dust from really toxic stuff like cadmium, chromium.

Mike Alkin: The argument, though, always centers on people thinking that the weaker energies are safer, more natural. That’s kind of understandable, I guess, until you look at the math, that wind turbines kill more people than nuclear power plants. Mike makes a really good point. It’s the energy density of the fuel that determines the environmental and health impacts. Yeah, sure. You can’t stand next to it. You can stand next to a solar panel, and you’re not going to have much harm. If you stood next to inside a nuclear reactor or right there at full power, you’re going to die, but that’s why they’re contained.

Mike Alkin: When it comes to generating power for billions of people, the reality is that producing solar and wind collectors, spreading them out over really large areas, has vastly worse impacts on human and wildlife. I like the way Mike phrases it. He talks about when he writes and when he speaks, if you watch his TED Talks, he talks about it over the last several hundred years, the evolution of humans moving away from matter-dense fuels towards energy-dense ones. You move from renewable fuels, like wood, dung, and windmills, and towards the fossil fuels of coal, oil, and natural gas, and eventually to nuclear power.

Mike Alkin: That energy progress is overwhelmingly positive for people’s standard of living. If you think about it, and I had not thought about this till I was talking to Mike and had read some of his stuff, as you stop using wood fuel, you’re allowing the grasslands in the forest. They grow back. The wildlife returns. As you stop burning wood and dung in your homes, you no longer breathe the toxic and indoor smoke. As you move from the fossil fuels to uranium, you clear the outdoor air pollution and reduce how much you heat up the planet. Nuclear, by what it does, is a revolutionary technology. Really a historical break from fossil fuels, which he argues is significant as the industrial transition from wood to fossil fuels before it.

Mike Alkin: But the real issue, and what we all deal with if you are pro-nuclear, is that it’s unpopular. For the last half a century, you’ve had this concerted effort by anti-nuclear weapons campaigners, misanthropic environmentalists as Mike calls them, and the fossil fuel industry to scare, to fear monger. As Mike argues, and I agree, in response, the nuclear industry has battered wife syndrome. They’re constantly apologizing for what should be its best attributes: waste, safety.

Mike Alkin: You’ve seen the nuclear industry promoting the idea that in order to deal with climate change, we need a mix of clean energy sources, including solar and wind. They have no cohesive message because that’s not accurate. You don’t. They could do it all themselves, but they just want to get somebody on their side. The real reality is France shows that moving from mostly nuclear to a mix of nuclear and renewables leads to more carbon emissions because you’re using more natural gas. Because the intermittency, you need peaking plants. You have coal, but it’s usually natural gas. It’s much higher emissions, higher prices.

Mike Alkin: The smart guys are the oil and gas guys. They politically align with the renewable companies. They spend a ton of money on promoting solar to these environmental groups for PR and all that stuff. If you think about it, it makes sense. If you become active on climate change and you gravitate towards renewables, it’s natural. It’s harmonizing with society and the natural world. I love that Mike points out it’s kind of like going to the supermarket, and you’re buying all-natural stuff. Again, just like the stuff you buy in the grocery store that says all-natural, you got to really read the label, and you got to start asking questions.

Mike Alkin: There’s a good piece in the MIT Tech Review last year. It talked about the battery storage because that’s what you need to get grid-scale renewables. You need storage for when that wind isn’t blowing and sun isn’t shining. In California, you’re going to have … I think it’s late 2020. I think Moss Landing comes in. It’s going to be a 300-megawatt facility. It’s one of, I think, four, giant, lithium-ion projects that PG&E has going. You’re seeing a lot of these projects or a growing number of these efforts taking place around the world. There’s all this optimism that these giant batteries are going to allow wind and solar to displace a growing share of fossil fuel plants.

Mike Alkin: But, there’s a problem with that. The batteries are way too expensive, and they don’t last nearly long enough, which limits the role they can play in the grid. If anyone plans on relying on them for massive amounts of storage as more renewables come online, rather than using a broader mix of low-carbon sources, no-carbon sources, nuclear, maybe natural gas with carbon capture, it’s simply going to be, again, using fourth-grade math, uneconomical.

Mike Alkin: For all the Green New Deal and all the other stuff that’s out there, and all the excitement about the renewables, who’s going to pay for it? If you think about the battery storage technology today, it’s very limited. It’s a substitute for peaking power plants really if you think about it in reverse, fueled typically by natural gas. If you really think about the role that these renewable plants can play, it’s really a peaker role.

Mike Alkin: I think the projections are the California storage projects could eventually replace three natural gas facilities, two of which are peaker plants. But when you start to get beyond that, your batteries run into real problems. You get diminishing returns when you add a lot of battery storage to the grid. If you think that coupling battery storage with renewable plants, for large, flexible, coal or natural gas, combined-cycle plants, when they’re a weak substitute … The others can be tapped at any time. They can run continuously, and they can vary output levels to meet shifting demand throughout the day.

Mike Alkin: Lithium-ion is too expensive for that, but you also have limited battery life, so it’s not well-suited for filling gaps during the days, weeks, even months when wind and solar generation isn’t cranking. You see that problem in California. Wind and solar fall off of a cliff during the fall and winter months, which, as the MIT piece points out, leads to a very critical problem. When renewables reach high levels on the grid, you need far, far more wind and solar plants to crank out enough excess power during peak times to keep the grid operating throughout those long, seasonal dips. That requires banks upon banks of batteries that can store it all the way until it’s needed, which becomes astronomically expensive as they point out.

Mike Alkin: Now, California is on track to get half its electricity from clean sources by 2020, and they want to get 100% by 2045. Then some work was done by the Clean Air Task Force, which is this Boston-based, energy policy think tank, and they concluded that reaching the 80% mark for renewables in California would mean massive amounts of surplus generation during the summer months, requiring 9.6 million megawatt-hours of energy storage. Achieving 100% would require 36.3 million. They currently have 150,000 megawatts.

Mike Alkin: Again, reaching the 80% mark for renewables would mean massive amounts of surplus generation during the summer months, requiring 9.6 million megawatt-hours of energy storage, and achieving 100% would require 36.3 million. They currently have 150,000 megawatt-hours of storage, and that’s mainly pumped hydroelectric storage with a small share of batteries. The fourth-grade math behind it, building the level of renewable generation and storage necessary to reach the state’s goal, would drive up costs from 49 per megawatt-hour of generation at 50% to $1,612 at 100%. That’s assuming lithium-ion batteries will cost roughly a third of what they do now.

Mike Alkin: So, the system becomes completely dominated by the cost of storage. You build up this huge storage machine that you fill up by mid-year, and then you just draw it down, this huge capital investment that gets utilized very little, which dramatically increases the cost for consumers. There was a study last year in Energy & Environmental Science which found that meeting 80% of U.S. electricity demand with wind and solar would require either a nationwide, high-speed transmission system which can balance renewable generation over hundreds of miles, or 12 hours of electricity storage for the whole system. Cost, $2.5 trillion.

Mike Alkin: $2.5 trillion. Where’s that coming from? We’re just talking about the land usage. Let’s do some math. A 1,000-megawatt nuclear facility needs about one square mile. There’s no U.S. wind or solar facility that generates as much as the average nuclear power plant. We just talked about one going up in California, 300 megawatts. So, 1,000 megawatts, a gigawatt, is three times bigger.

Mike Alkin: If you’re looking at a wind farm, a wind farm requires up to 360 times as much land area to produce the same amount of electricity as a nuclear energy facility. Solar photovoltaic requires up to 75 times. There’s a 2015 report called Land Requirements for Carbon-Free Technologies, and it compared the land area that various types of electricity generation facilities would require to produce the same amount of electricity as a one gig nuclear power plant, 1,000 megawatts.

Mike Alkin: A nuclear energy facility has a small area footprint requiring about 1.3 square miles per 1,000 megawatts. Now, they took that figure based on the median land area of the 59 nuclear plants in the United States, the sites, and they have an average capacity factor of 90%, obviously, much higher than the intermittent sources of wind and solar. Which, wind farm capacity ranges from, what, low 30s to mid-40s, depending on the differing wind resources in a given area. You get some improvements in turbine technology, so on and so forth. Then your solar PV, high teens, high 20s.

Mike Alkin: Taking capacity factors into account [inaudible 00:38:27] everything, a wind farm would need an install capacity between 1,900 megawatts, and 2,800 megawatts to generate the same amount of electricity in a year of a 1,000-megawatt nuclear energy facility. That facility required 260 square miles and 360 square miles depending on the 19 to 2,800 of land. For solar PV, you need an install capacity of 3,300 to 5,400 megawatts, to match a 1,000-megawatt nuclear facility requiring 45 and 75 square miles. I’ll put that in context. The District of Columbia’s total land area is 68 square miles. Manhattan is 34 square miles. If you take in the five boroughs, it’s 305 square miles.

Mike Alkin: There’s no wind or solar facility currently operating in the U.S. large enough to match the output of a one-gig reactor, 1,000 megawatts. Again, though, people think, and it triggered me, this guy who was emailing me was the second part of a conversation I was having about this, but with a good friend of mine, who is a utility executive that does not have nuclear power in their mix. He’s a good friend of mine. I’ve known him for many years, and I have great confidence in his intellectual honesty and his knowledge.

Mike Alkin: We had breakfast, and I said, “How you doing?” He said, “I’m good.” He said, “A lot of hysteria over green energy, UN Climate week.” He said, “It’s just crazy when you think about what people are being sold out of fear, that you’ve got this view on the renewables with the costs that are impossible to get at any size scale.” And he says, “It’s all being shoved down their throats by politicians and subsidies.” He said, “I have no doubt 50 years from now, whatever it is, that technology will keep advancing, and improvements will keep coming, and that we’ll get better and cheaper way over time.”

Mike Alkin: He said, “But you’re not letting it grow organically. It’s being fed GMO by the politician” You know the GMO modified, genetically modified, it’s being modified by the politicians because they want to pander to their constituents and it’s just not affordable. This utility has a ton of renewable projects. He said, “What if you went to industry in 1990, and said, ‘By 2008, you have to have a handheld device with computing power … ‘” Not by 2008, he said, “If in 1990 you went and said, ‘I want, in the next few years, a handheld device that has enough computing power that took the men to the moon, that could have cameras on there, that can do everything, but it’s got to be done in a few years. If we don’t have it, we’re not going to be able to function as a society … ‘”

Mike Alkin: Steve Jobs figured it out. They came up with something. It took them 20 years, but it wasn’t being mandated to be done immediately, and the disruption that it causes. All of these dollars are being put into this, and all of this fear is being put into it on the renewable front. Who’s paying for it? Just something to think about. Google a bunch of stuff. Look at the real math. Look at different studies. Avoid the headlines. Read the headlines. Take that view, and then see if there’s an alternative view to it, and apply some fourth-grade math. Take out the fear and apply some logic to it. If you conclude that then wind and solar are the way to go, renewables are the way of the future, and they probably are at some point, and some level of them in some mix, then at least you’re informed.

Mike Alkin: Anyway, I just wanted to share that because I had a couple of these two interactions this week. I thought first with my buddy, the utility executive, and then secondly, the guy who’s been emailing me, which isn’t going to last for that much longer. Anyway, great time of year. I don’t even know what to watch between the NHL season starting. Islanders start off one and one. You’re going to be hearing a lot from me this year on the Islanders. Win or lose, I’m committed to keeping my opinions out there.

Mike Alkin: I had two playoff baseball games yesterday. We had NFL football. Maybe Saturday we had both college football, NHL, baseball playoffs. It’s a great time to be a sports fan. Well, that’s it for me. I hope you have a great week. Get some good sports watching in. We’ll see you next week. Thanks.

Announcer: The information presented on Talking Stocks Over Beer is the opinion of its hosts and guests. You should not base your investment decisions solely on this broadcast. Remember, it’s your money and your responsibility.