In the late 2000s, researchers at Bond University in Australia conducted a study of venture entrepreneurs whose startup businesses had failed.

They wanted to test a theory… and see if the entrepreneurs would exhibit a psychological phenomenon called “hindsight bias.”

The researchers hypothesized that failed entrepreneurs would look back at their experience and say they “knew all along” their businesses would go wrong—despite their previous optimism about future success.

The idea was to show that humans tend to use the benefit of new information—information our brains deem as “obvious in hindsight”—to judge our past decisions.

Before the failure of their ventures, 77.3% of entrepreneurs believed their startup would grow into a functioning, operating business…

But, after their startups failed, only 58.8% recalled that they’d initially believed their business would succeed.

In other words, many judged their past decisions based on information they didn’t have at the time.

This psychological phenomenon—known as hindsight bias—is something we’ve all experienced at one time or another…

We tend to look at past events as if they were easily predictable… even if we had no way of knowing the outcome in advance.

And this type of bias can be particularly costly in finance…

It can lead us to misunderstand reasons for specific market actions or events… and discourage us from making rational, well-researched decisions.

Let’s take the Great Recession as an example: At the time, many investors and pundits ignored the warnings… Yet today, they claim they saw the signs and knew trouble was coming for the housing and stock markets.

The failure to recognize past mistakes can lead to overconfidence in predictive abilities… leading us to ignore the next set of warnings for a big macroeconomic event.

But there’s one simple method you can use to help overcome biases: dollar-cost averaging (DCA).

Dollar-cost averaging is buying selected assets (stocks, ETFs, or mutual funds) on a set schedule (such as annually, quarterly, or monthly)—regardless of the price.

This probably sounds familiar if you have a 401(k)… where you automatically and systematically invest a set percentage of each paycheck into a predefined group of assets. While the dollar amount stays the same, the number of shares you buy changes all the time… depending on the price.

So when the price of an asset is down, it means you automatically pick up more shares… while when the price is higher, you purchase fewer.

What does this mean?

That you avoid overpaying at the top… and lock in more shares at a discount near the bottom.

In other words… DCA turns market declines to your long-term advantage.

And here’s the best part: Because this method is based on pre-scheduled investments, it takes predictions—and therefore, hindsight bias—out of the equation.

In many cases, you’ll also end up with a lower per-share purchase price than the market average over the same time.

Here’s how it works…

Let’s say you have $4,000 to invest, and you bought 40 shares of a made-up company we’ll call Acme at the beginning of the year at $100 per share.

At year-end, the total value of your investment will depend on the market price.

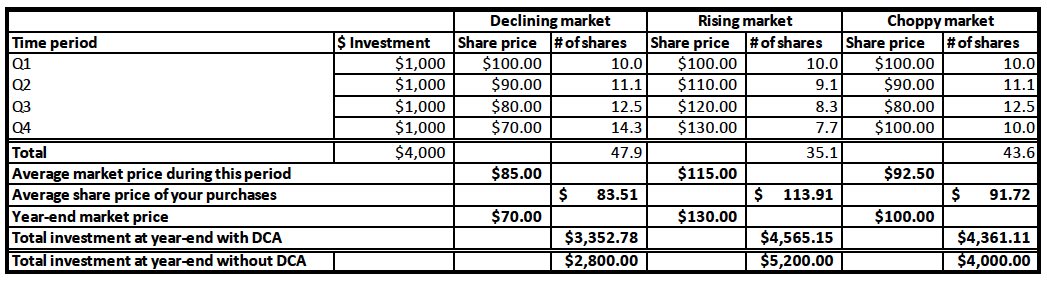

How DCA works in a rising, falling, or fluctuating market

With DCA, depending on the market path, at year-end, you’ll end up with fewer or more shares… and the value of your Acme investment will differ with each scenario.

A declining market would result in a larger number of shares… at a lower average price.

In a rising market, you’d end up with fewer shares… but your per-share cost will be lower than the average market price during this time.

And in a choppy market, you’d likely end up owning more shares than by simply investing a lump sum in the beginning… and at a lower price, too (the end result will depend on the actual path the market takes).

The bottom of the table shows your gains/losses if you didn’t use DCA… and invested the entire $4,000 at the beginning of the year. As you can see, you’d only be better off if the market kept rising… and not by a wide margin.

The bottom line: DCA can help you invest for the long term… and use periods of market volatility to your advantage.

Most importantly, with this method, you don’t need to predict what the market will do. It helps you overcome your biases… and keep emotions out of your investment decisions.

For more investing strategies and market insights, tune into Wall Street Unplugged Premium each week.