Nothing is linear… especially stocks. And price doesn’t necessarily equate to value…

This understanding is critical to finding good investment opportunities where others aren’t looking.

Quite often, the very best values will make your stomach churn early on in the investment.

Join me and two grizzly, seasoned, deep-value investors: Chris MacIntosh of Capitalist Exploits and Harris “Kuppy” Kupperman of Praetorian Capital [22:08]. We discuss exciting, under-the-radar investment themes that most others have no interest in—yet.

Pull up a stool, pour yourself a cold one… For the next hour and change, we’ll kick around some of the best risk/reward opportunities in the market.

Chris MacIntosh & Harris “Kuppy” Kupperman

Ep. 69: If you want to invest with the big boys… start here

The Mike Alkin Show | 69

If you want to invest with the big boys… start here

Announcer: Free and clear of the chatter from Wall Street, you’re listening to Talking Stocks over a Beer, hosted by hedge fund veteran and newsletter writer Mike Alkin, who helps ordinary investors level the playing field against the pros by bringing you market insights and interviews with corporate executives and institutional investors. Mike sifts through all the noise of mainstream financial media and Wall Street to help you focus on what really matters in the markets.

And now, here’s your host, Mike Alkin.

Mike Alkin: It’s Tuesday, August 6th, 2019. Hope you’re having a nice summer. We’re getting a bit of a reprieve here in the northeast. Actually, we sat outside last night in our yard with the fire pit on. And if you listen to the podcast, you know that I am not a summer guy. I am a gimme some crisp weather guy. So we had the little semblance of what’s to come, or a little indication of what’s to come. So I was pretty pleased with that.

But, I was thinking, we bought a new car this past week, and I have to tell you that the whole experience, I don’t know why it shortens my patients in the angst knowing that I’m going to have to go through the process. Sometimes we know what we want, we just go get it. But this time after having my wife, she’s hauling kids around town and I’m often taking my son on road trips for travel, lacrosse, and then they have a lot of friends, a lot of kids and, and so seven seats is something that was important to my wife. Minivans are out, she’s anti minivan. My kids are anti minivan.

So it was, we were looking in our last car, we’ve had, I think three, well, my wife’s car, she settled on a Buick Enclave. And when we first bought it, maybe it was two times we’ve gone back to the well on that one. But you think Buick, you’re like, oh God, your father’s Buick. But they’ve come a long way. They’ve done a nice job, but they have easy access. They have captain seats in the second row, so you could walk right back to the third row in there. It’s spacious.

But this time around, the kids said, when we were in LA a few months ago for vacation, we rented a Mercedes SUV for the week. And the kids liked it and my wife liked it. And so then the kids said, “Well, just go with the BMWs and the Audis.” And I’ve had BMWs in the past. And we thought maybe Volvo. So we said, “Let’s take a fresh look at what we want to get.”

And I just hate the car shopping experience. I don’t being sold to. I like being advised or consulted and I appreciate it. I absolutely appreciate people have a job to do. And it’s got to be hard being a sales car salesperson now because most people, I’m sure, at least take a little bit of time to educate themselves as to what’s out there with the Internet. You can do a lot of comparison shopping and reviews and all that stuff.

But it was interesting. A few times. My wife popped into a dealer where if I couldn’t get there with her, she’d pop in and, and my wife’s a very educated woman and she would come home and say, “I want to scream.” She said, “If I was called honey or sweetie one more time, and people talk down to me they think I’m a dummy,” and my wife’s the brains in my household. So right away, a guy would lose interest and she’d say, “Okay, well, if we’re going to look at this brand, we’re going to a different dealer.”

So anyway, we looked at them all, went and looked at the Mercedes, BMWs, the Audis, the Volvos, and you name it, and we were back to the Buick Enclave. For us, it was great where you get that … All the others are, I mean, obviously they’re very nice cars, safe, good quality. But the price disparity was crazy when you look at the access, what we really wanted, I know it sounds ridiculous, but the most important thing was how do we get five or six kids into that car with ease, where they don’t have to do gymnastics to get into that third row. And the Enclave made some really nice upgrades. The look, the last model wasn’t that great, but they did a nice job on the look on outside and on the inside, and they say they made it look extremely nice and we sat in the car, the new one, because that was the last one we went and looked at and said, “Wow, this isn’t that far behind the others, and it’s basically a $40,000 difference in the price of the car.”

So, that was the past week. But when I walk in, I say, “Listen guys, sorry, I’m a numbers guy for a living and here’s what I know in terms of pricing and so on and so forth.” And I try and shortcut it a little bit. And the whole process just gives me angst.

Anyway, get our new car. I was thinking, I think you all know that … all know, listen to me, that’s so presumptuous. I sound like a jackass. For those of you who do listen to the podcast, I’m a New York sports guy. Now, interestingly, I’m not a fan of living in New York. We live here by default. My wife’s family is here. We’re both from here, but I’d live a thousand other places. And I think so my wife now, but the kids are ingrained in middle and high school, so, until they’re out, we’re not going anywhere. But I grew up just a die hard, Met islander and Jet fan and Knick fan. And being in New York sports fan is tough, because most of the teams suck unless you were an [inaudible 00:06:48] fan in the ’80s.

But you come into every season holding out hope, and I mean, the Mets were in the World Series a few years ago, but the Mets came into the season with a lot of promise, and a new GM who used to be a sports agent came in as a general manager, pretty cocky guy, and was very confident, called the Mets the team to beat. And at the halfway mark, the Mets were about 11 games under 500, and for those of you who are not baseball fans or don’t watch a lot of it, that’s poor, 500 mean 50-50 on your record. But they were a well below and struggling. They couldn’t get out of their own way going into the all-star break, which is about the halfway mark of the season.

And it’s interesting, because I was thinking of how sports equates to the capital markets and stocks. I am an avid listener of sports radio, and I don’t know why because it drives me nuts, but I think it’s entertainment value. But I’ve been listening to WFAN radio here in New York, which is probably one of the first sports stations in the country, and it’s big, it’s probably the largest. And I’ve been listening since it came on the air, I think in the late ’80s. And the format is they have their different hosts and many of them are here for many years. And it’s a call-in format, and it’s so interesting to hear now that the host, they’re Met or Yankee fans, and the fans obviously in New York are Met or Yankee fans, and the Yankees are having a great season.

But as the season wore on, the Mets fans were calling up just hammering the new GM, the general manager on its first year on his job. He made a trade that didn’t look good so early in the season and probably is still not great so far, calling for the managers hosting his second year in, this guy’s a bum, that guy’s a bum, the other guy’s a bum. They need to do this, this, and this, a constant barrage. And if you’re not from here, but if you’ve visited here or you hear people, you get some of these funky New York accents, which can just, it’s like nails on a chalkboard, but when you’re from here, you just get a chuckle out of it.

But people get outraged, and there’s debates and fights on the radio and I’m in the car a fair amount. So I’m listening to it, and I get a chuckle. I’ve never once called in in I don’t know what, 30 years. I’ve never called, 30 plus years. I’ve never called in. But I listen a lot.

And so now all of a sudden, the all-star game comes, and the Mets couldn’t get to the break fast enough. They get three or four days off, the league does. And since the all-star break, the Mets have the best record in baseball, the pitching staff has their lowest earn ran average in baseball, and there were 17 wins and six losses. And they’re back in the playoff race for the end of the season, and there’s 50 games to go maybe.

And now all of a sudden the sports radio is lighting up with excitement, and everyone loves it. And Mickey Callaway, the manager, now he’s doing a pretty good job and Brodie Van Wagenen, the GM, his plan is starting to come together, and the guy who was in the slump earlier in the season, now he’s really starting to turn around and start to hit, and everyone gets excited.

And as I listen to it, I think of investing, I think of momentum investing. I think of headline watching and headline reading and reacting. And the baseball season is 162 games. It’s a long season. I mean, they get to spring training, the pitchers and catchers get there in the middle of February, in all of March and a little bit of April, the fields in Florida and Arizona, have spring training, it’s a rite of passage for a lot of kids in America growing up, you go to a spring training game, family vacations down to spring training. And in the warmth, you come from the north, you go down for a week into the south or the southwest and you watch the guys getting ready for the season, and then the season starts in early April and they go through the end of September and playoffs go and to October. 162 games play, and then you get through the summer, the dog days of August, where it’s brutal and they’re playing back to back, and people might look at a baseball game Saturday, stand around a lot.

Yes. I played a lot of baseball and it takes a toll on your body after a while, because a lot is fast twitch, start stop. Sudden bursts in your body as a player can start to wear down over a long season. But the similarities, I think about what I read on Twitter or what CNBC or what financial radio has. It’s all headline driven. It’s as though you’re supposed to perform today. It acts as though the world is linear. This season is linear. You have a good team on paper, you should just have a great season. That’s it. You should go wire to wire and league to league and lead your division.

Same thing when a company, right? Jeez, it’s a company. They have 10,000, 5,000, 20,000 employees or an industry that’s going through a dynamic change. It should go just like it gets planned, right? Wrong. That’s not how it works. And like those people calling in calling for Mickey Callaway and Brodie Van Wagenen’s job, and this guy’s a bum and that guy’s a bum, the other guy should be benched. It’s just like with a company. Now, if you have a value or a deep value or a contrarian investment style, what you’re trying to look for is the Mets when they’re 11 or 12 games under 500. A, you’re looking for a talented roster if you’re looking at baseball, talented roster, but stumbling and struggling and you can’t figure it out, something’s wrong. Something’s not firing right, but it has the core to do something right.

If you’re a deep value investor, you’re looking for a business that’s stumbled. It could be in a deeply cyclical industry where supply and demand needs to work itself out and it’s trying to sort its way around the bottom, or it could be a more secular-type business, secular being less cyclical. But it could have stumbled. It could be self-inflicted, it could be temporary industry conditions and it’s down, and you buy it, and you’re looking to buy value. It doesn’t mean it’s going to turn around right away. It doesn’t mean it’s going to happen immediately. But in the world of investing, you shouldn’t be looking at what’s your risk-reward but what’s my potential upside from this investment opportunity, and what’s my potential downside? So what’s my risk? How much percent down, and what’s my reward? How much percent up?

And then if you have that stacked in your favor, then you wait, right? Some investments in some really deeply cyclical industries, you can see things get so out of whack because it’s emotion, right? We’re on sports radio, that guy calling in can’t make the trade he wants to, he can’t fire the general manager. So he’s got to sit and he’s got to wait. And he could either choose to stay a fan of that team or he cannot, he could leave, go find another team. That typically doesn’t happen in sports, but it can. But to listen to sports radio, there’s so much raw emotion and people can’t sleep and they wanted to … but their money’s not at risk, only their entertainment.

In the world of investing, when people are investing their own money, that’s even at a whole different level. And then they’re getting bombarded with the financial media, with Twitter and debates and the message boards, and now when their own money is at risk, now the emotion takes over at a whole different level. And just like when the Mets were 12 games under 500, when your stock is down 20%, 25%, or pick a number, if you haven’t done the analysis or spent the time to understand what your risk-reward is, and follow price action, “Stocks down 20%, I must be wrong.” And then you listen to the people when it’s down 20% everyone is piling on. Sports radios, you’re 12 games under 500, fire the bum, get rid of him, change the roster. When stock’s down 20%, 25%, fire the CEO. Something must be wrong. I made a mistake in the investment is what people’s logic tends to be.

But it’s all driven by emotion. It’s driven by price action. Price action in sports is your record. It’s a long season. Think about it. Now all of a sudden the Mets have the best record in the second half. And like I said, you should hear sports radio. You should see the columnists writing their stuff. Three weeks ago, this team was written off for dead, and they put one win together and another and another. Then they lost a game. Then they won three or four more, then they lost one. But now the momentum is picking up on the team, you could see the confidence in situations where they weren’t performing, in clutch situations, now they are, and you watch the games at City Field and you could feel the excitement through the TV. You could hear the buzz. If you were watching that game four or five weeks ago, crickets. And it’s here.

So nothing’s changed. The talent’s the same. The GM is the same, the manager’s the same. But it’s a long season and things happen. And an educated fan looks at it and says okay, well let’s take a look. Here’s the roster. These guys, most of them, not all, but most of them have a body of work over a period of years. And sure, sometimes people have career years, sometimes they have terrible years, but for the most part they’re going to start to get it together. Like investing. Why did I make this investment? What was the risk-reward? Did I think it could go down in 20%, 25%, 30%, whatever industry or company you’re looking at?

If that’s what you thought it could get, when it gets there, you want to understand why did it get there? Was it market driven? Was it fear driven? Did they stumble? Did they lie? Did they not say what they were going to do? If your original thesis was wrong, and it happens, it’s definitely going to happen. If your thesis is wrong and you have to look for a new reason to own it, then you sell the stock. That’s call it thesis creep. You have a thesis, you have a risk-reward. It gets down to your certain price level. It gets there, you re-examine and say, is my thesis hold? Yes. Is there a reason why could go down further? Maybe, probability weighed that, but is the reason that I saw and it’s the same risk-reward intact?

Then you’ve got to filter out the noise. Think about being Mickey Callaway, the manager of the Mets. Or if you’re in a lineup and you’re playing and you’re having a tough season, if you’re listening to the press, if you’re listening to the fans, especially in New York, I mean, if you’re playing in Kansas City, great city, by the way, but if you’re playing in Kansas City and you have three reporters in the locker room, if you’re playing in New York, after a game, you got 20. You’re getting bombarded with questions, but if you’re on that field and you’re struggling, and you were to listen to the press and let the pressure get to you, you’re going to press and you’re going to make more mistakes.

If you’re an investor and you are following price action and you’re listening to sports radio, or the equivalent of, Twitter, CNBC, Bloomberg, and you’re listening to the guy who came on, the portfolio manager who you don’t know from Adam, you don’t know anything about him. You have no idea if he’s good or if he sucks, but he’s pitching something and it might be counter to what your view is and you’re like, “Oh my God, I’m wrong.” You can’t do that. You have to understand what you own, why you own it, what the risk-reward is. If it drops down, you need to understand what your thesis was. If your thesis has proved incorrect, then you sell. If not, you might have an even better opportunity than you did. But you can’t let the emotions of the moment. It’s a long haul. If you are a deep value contrarian investor, and in any deeply cyclical industry, you got to be playing the long game. You got to know that going in and price action shouldn’t dictate what your decision making is. That’s already got to be factored into your risk-reward.

So anyway, I thought it was a very interesting comparison as we were seeing it swing now, because now what’s happening is the bandwagon starting. Everyone’s jumping on the bandwagon, the McMahon wagon. “We always thought that they would finally get it together.” You listen to call-in shows ringing from Brooklyn. “Yeah. I was sensing that it was turning. I knew. I told my friends that you just got to hang in there.'” Okay. Sure you did. Because you remember these same callers, and I’m picking a name. I’m making up a name. It could be anyone from anywhere, but you remember these names and the same guys who are now jumping up and down about how good it was three, four weeks ago, they were calling in and saying fire the bums.

So, emotions can play a part in it and you just have to filter out the emotions. And I have a couple of guys coming on the podcast in the interview that we’re going to bring on now. And you’ve heard both of them before, they’re two friends of mine, Chris MacIntosh and Harris “Kuppy” Kupperman, and before the interview and during it, you’ll hear, Chris always says, “Hey, the greatest risk in any market is linear thinking in a dynamic world.” And he’s talking about it, he says, “It’s so crazy right now, the stuff that’s most critical to civilization energy is the cheapest it’s ever been on a relative basis.” Yet it’s out of favor. If it were baseball, they’d have a 12, 15, 20 game under 500 record. But is it going to turn? I don’t know. Let’s hear what the guys have to say.

Mac, Kuppy, welcome to the podcast.

Harris K.: Hey there.

Chris MacIntosh: Hi, man.

Mike Alkin: I was thinking, we talk frequently, and wouldn’t it be nice to give a window into people listening on the podcast because if they heard our conversations, they just think we’re three grumpy old men, just little curmudgeons who deep value side on the long side and think everything is crazy on the growth side, on the short side. And I thought, “You know what, let’s, bring them in into one of our conversations.”

So, Chris, let’s start with you. What’s wrong with the investing world as see it? What are some of the bigger things that sit in your [inaudible 00:23:49] on a regular basis? Where are some of the opportunities because of that, that you think are occurring right now?

Chris MacIntosh: Jesus, where to start? [crosstalk 00:23:56]-

Mike Alkin: … any time.

Chris MacIntosh: Yeah. Well, I guess if you’re going to encapsulate into one thing, it’s a narrative. We will have deflation up the wazoo until kingdom come, and nothing’s going to stop that. I think that’s the prevailing narrative, and then everything rolls off of the back of that. So if you think that that is true and that’s what the world is going to look like, then, well, you’re not going to be expectant of anything that would produce inflation, and the only way you really make money in that sort of market is how you’ve made it in the last decade, which is, you buy a shit like Tesla and WeWork and Beyond Meat and anything that actually acquires market share, preferably if they do so at a massive loss. The greater the loss, that’s the better model because they’re acquiring more market share than their competitors.

And so you’re coming to get those-

Mike Alkin: Let me just stop you there for a second. And Kuppa, you jump in. You guys, like me, were around for the dot-com era, and you saw businesses being valued on a per eyeball basis. And at the time when we were sure of these things, it was painful, but you’d look and say, there’s got to be some common sense that comes back to the market. Eventually it did. But here, your bigger growth companies, the more they lose, the more the market appreciates it because they keep growing. And they almost get a free pass, that you have to grow and everyone goes to Amazon by the way. “Well, look what Amazon did. In the early days you’re losing money and that’s just part of it and you’re going to eventually catch up to it.” How do you guys respond to that? Kuppy, when you look at the [crosstalk 00:25:58]-

Harris K.: Let me talk about Amazon, because I think there’s a lot of mistakes about what Amazon was. And mind you, in 2002, I made a basket of bombed out dotcoms and I owned some Amazon, and about tripled. And I sold it and I felt really smart about myself. I think I sold it at about 25.

Mike Alkin: That was a great trade.

Harris K.: Phenomenal trade, actually. But when you look at Amazon, keep in mind, back then they didn’t have AWS. It was just a retailer. And as they grew, they had negative working capital. So their own vendors funded them. And the losses, yeah, they lost some money. Everyone remembers that, and they had some converts and people were worried that they wouldn’t pay them off, but their losses were in the tens in at worst, hundreds of millions. I don’t have it in front of me, but I doubt they lost fully $1 billion at the worst of it all.

And then they inflected it for about a decade they ran the business sort of breakeven, some quarters were up, some were down, but it was a breakeven-ish thing where from a working capital standpoint, someone else is funding them. So from a cash basis they had plenty of cash coming in.

And so that’s the Amazon story. They really didn’t lose that much money. Everyone has this view that Amazon lost as much as Tesla and it eventually hockey sticked, but that’s not really the truth. Amazon ran breakeven and used vendor financing to reinvest in the business and grow. Then you look at some of these other things, like, well, Tesla’s the most obvious. They just literally lit money on fire. And the more money they light a fire, the more excited people get. They’ve lost money at three different car models they’ve produced. And everyone’s excited that they’re going to come out with a pickup truck now. People have lost their mind.

Mike Alkin: But you’re right, they go back and reference that and everyone gets pointed to the initial unicorn in the market. And everyone says, “Well, if they did it, that’s okay.”

So how are you, Kuppy, how do you in a market where it’s been hard to make money as a value investor for quite some time now, right?

Harris K.: Impossible.

Mike Alkin: Passive investing has taken over. Or it’s almost impossible. And anything that has growth, whether losses be damned. So how do you navigate the markets in this environment?

Harris K.: Oh wow. I’ve been up the last few years, which I’m proud of because a lot of value guys haven’t. And there’s lots of ways to think of value, and I’ve been finding stuff that’s just so bombed out that it really can’t go too much lower, like the Aimias is of the world, or I’ve found some growth stuff. In a world where everyone’s starved for growth then bid these things to crazy prices, I’ve had winners with the join to Viamed. I bought Viamed at three times earnings. It was growing fast. You couldn’t lose money. That opportunity lasted about a month. I bought as many shares I possibly could. There were many days where I was like a third of the volume.

There’s still places where there’s opportunity because the markets aren’t that efficient still. I know people claim they are, but they’re not. And you do have inflections in various markets, and there’s things you could do. I caught a huge wind in Scorpio Tankers, because the computers can’t see forward and see this IMO 2020 thing that’s about to hit them over the head in Q4. And so there’s stuff you can do, you just got to work harder and think smarter about it. But the worst possible thing you could do is buy a company at three times earnings with a bunch of cash flow in a buyback, because the market hates that.

Mike Alkin: Right. Exactly. How about you, Chris? How do you think one who is a contrarian, one who has a value bent, what opportunity do you see? And I know some of the things we’ve talked about is we’ve talked about how the shale plays don’t make sense and you’ve been very attracted to offshore oil and gas. Could you walk through what your reasoning is there?

Chris MacIntosh: Look, if you go back and you think about what’s worked, it’s been this idea that you can have a business where you basically go out and you sell hundred dollar bills for 90 bucks. And so you’re going to lose 10 bucks on every trade, but you’re going to do a shit ton of volume. Right? Because who doesn’t want that deal. And so everybody that walks into your shop’s going to buy a deal, because they like money, but you’re going to do massive volume and your user growth is going to go up the wazoo, you’re going to look a Twitter or an Uber or something like that. And then ultimately you can go and you can hold in Goldman’s and do an IPO and the cycle is going to go out the door and you can just leave it to the dumb retail bag holders. That’s pretty much been the business model.

And when that’s taking place, the idea of going into something that is much, much longer term in nature becomes less attractive. And so if you think about the stuff that that requires significant capital expenditure, and Kuppy just mentioned Scorpio, which is in the shipping space and shipping’s been decimated, and there’s this very, very little ability to actually finance in the shipping industry. In fact, there’s very few analysts that are left in that space. And there’s even now protocols against actually financing for many of these large institutions.

And the thought of that’s around the whole fossil fuel. We’re all going to die because some fucking 15-year-old teenager in Sweden says that that’s the case and we’re all listening to it for some goddamn reason. But the other is just that there’s no critical thinking around this stuff. And it’s very, very difficult. Anything that is capital intensive, and that then feeds us into the energy space, requires a lot of hard work, it requires a lot of capital, and it requires a lot of time, because you can’t turn the stuff on very quickly. And so, I’m not really sure what it is that’s driven the market’s attention span so long. Maybe it’s a combination of social media and gaming, and I don’t really know what, but I do know this, I do know that back in the ’70s or I think it was the ’80s, the average holding period for an equity was 10 years and today it’s under four months.

Now, all of us guys on this call know very well that the fortunes or lack of fortune for any particular company does not change in four months. Unless you get hit by a tsunami or something of that nature, it just does not happen. And so you think, “Well, if that’s the case, then why the hell are people moving in and out of their positions in such a short timeframe?” And it comes back to this market that we have today where people will be buying Beyond Meat because it’s what’s running across the headlines, or they’ll waiting for WeWork to list or they’re buying Tesla or something like that because there’s a lot of media coverage around it.

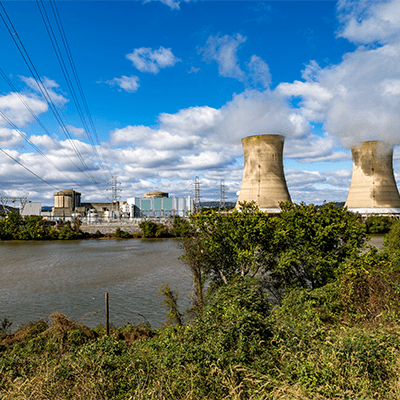

And that’s all fine and well, and I think by and large all of us tend to just ignore that, or we just laugh at it, but we don’t typically go against it, because it’s pretty hard to go against a tidal wave of perception. And so you look at what doesn’t get attention in that environment and what hasn’t got attention, and it gives everything that’s basically got huge capex. Incidentally, it’s a lot of stuff in the energy space. And so, Mike, you’ve done an enormous amount of work in uranium space, and certainly I’ve never met anybody that’s done more detailed analysis and fully understood that market then you have. But you’ve got the similar sort of dynamics there as you have, really, across much of the energy space.

So I guess I’m looking at a lot of things across that space. I mean, again, I mentioned a crazy little teenager in Sweden, but you’ve got this whole idea and it’s across the Western world that we’re going to, for example, remove ICE vehicles by, and you can pick your target zone. For some of them that’s 2030, some of them it’s 2025, some countries it’s 2040. But, we sat down here at HQ and we did some numbers on what exactly that would mean if any of these countries hit those sorts of protocols. And it’s just absurd.

There was actually a study that came up by a bunch of scientists at a university in Britain, can’t remember the university now off the top of my head now. In any event, excuse me, they said, “Okay, Britain’s just declared that they’re going to get rid of fossil fuel cars and all this fun stuff by 2030. What does that actually mean?” And they ran through the numbers, and what it meant was the requirements for the materials that would go electrification, just for Britain, and Britain’s small if you take the aggregate, which is all of Europe, Denmark, Sweden, a lot of the Scandinavian countries have all come out with these initiatives where they’re saying, “Oh yeah, we’re going to get rid of this and this is what we’re going to do by this date. Let’s go.”

And so if you bring it down and you just look at Britain, what it means was things like copper production. They were going to consume all the copper for an annual supply. They were going to consume 50% of all the cobalt that gets produced. They were going to consume, there was a bunch of rare earth, one of them was three times annual supply, things like this, and that’s just Britain. So you look at it and you go, okay, well one or two things going to happen. Maybe, if this is true, we’re just not going to need oil. We’re not going to need natural gas and we’re not going to need coal, any of these fossil fuels, we’re just going to run it battery technology, which ultimately comes from the electricity. So that’s fine. Then the prices of all those goods is going to have to not just skyrocket, but literally do what cryptos did. Seriously.

And so that then makes them extremely uneconomical. I think it’s probably fair to say that we will have a massive, massive global recession, if not depression, just because energy in the transportation of goods and services is massive and it impacts every single good and service that we all consume. So [inaudible 00:37:27] that’s probably not going to happen. Well, if that’s not going to happen in the current status of what people, although how the markets are viewing the, should we call it traditional energy space is completely out of whack.

And this is without saying what the electricity side of things looks like, because again, if you’re going to charge all your bloody batteries and you do somehow manage to get all of the copper and nickel and cobalt and everything else, let’s just pretend that you somehow got that, well, you still need electricity. So where’s that going to come from? So, that’s one of the most exciting places for us, is looking at that entire spectrum.

Mike Alkin: And what are your thoughts on the shale plays? And Kuppy, jump in here. Feel free.

Chris MacIntosh: I think to a certain extent shale’s similar to what you had in the uranium space with respect to underfeeding. It’s extra supply, but it’s coming from something, people have viewed this now on a linear timeframe. Firstly, they’re viewed, and we know this by looking at the fucking junk bonds, right? Because the way that those things were originally priced was that they were akin to finding a [inaudible 00:38:53] or a North Sea or something of that nature, which has substantially different decline rates. And so the way that those ones were priced was as if you found a traditional oil field. And now we’re finding that that’s all garbage. Most of these things are trading way below par. And I don’t like this. Kuppy, what’s it been? Couple of years since there’s been a junk bond issued in the shale space? I mean, basically the market’s [crosstalk 00:39:21]-

Harris K.: There’s been two or three, but there’s been no equity issued at all in two or three years now, there’s been a handful of junk bonds. Basically people have woken up and said, “Aha, this business model doesn’t make sense.” Yes, you could produce a lot of oil but it’s not economic. And when you look at a lot of these companies, and when oil was at much higher prices, they lost money. When oil is at lower prices lose more money. The accounting is very confusing. I mean, oil accounting in general is based on if you trust the reserve engineer or not. And what we’ve learned is that you can’t trust most reserve engineers, go figure.

So, you’re having a lot of these guys miss targets, and when you’re on the hamster wheel where you have to keep drilling in order to keep your production flat and you have to drill more to grow, as soon as you stop drilling, and this is the problem. I mean, when you think about it, guys like me are looking at these things and saying, “Why are you guys drilling? You’re putting a dollar into the ground against 75 cents out and you’re paying 9% interest rates to do it. Why don’t you just put your assets into runoff, pay off some debt, slow down, wait for higher pricing?”

The great thing about shale, when you think of it logically is that at today’s commodity prices you don’t make any money. So what you should do is wait for higher commodity prices. And because there’s a short time span between when you spot a well and you start producing, I mean you could literally just hedge it. So oil goes to 75, you lock in a bunch of future production with a hedge. Now you go and you drill it and you kind of know where you’re going to be, and you’d have some margin of error and still actually make money.

Why these guys keep drilling, even though they don’t make any money today, is that if they don’t drill, suddenly their EBIT x goes negative. And when your EBIT x goes, suddenly your borrowing base goes, which means you can’t drill more wells because the banks are looking at this EBIT x number and they’re not looking at other metrics as much. So you really can’t get off the hamster wheel ever. And besides, the bigger EBIT x is, the bigger your annual bonuses. So why would any CEO ever try to get off from the hamster mill?

Mike Alkin: Right. It’s in their DNA. Grow, grow, grow, production, growth. And they’ve been financed, right? I mean, thank you zero interest rate policy. I mean, it creates-

Harris K.: You see these guys, they trade down from 20 a share to a dollar a share, you go on the conference call and you’re like, “So these guys obviously going to cut spending, figure out how to increase liquidity, put it into runoff, cut costs.” And they’re like, “Yeah, we’re just going to drill faster.” And it’s like, what? You guys literally are not in compliance with your covenants. “Oh yeah. We’re just going to keep drilling. We’re going to find buried treasure.” [crosstalk 00:42:05].

Mike Alkin: But industries, when this happens, there’s ultimately the day of reckoning and we have hundreds of billions of dollars coming due in the next few years, how do you see it playing out?

Harris K.: I think everyone goes broke.

Mike Alkin: So from an investor standpoint, do you short certain shale plays or are you … Chris, I don’t want to put words in your mouth, but you see the pending collapse in shale plays as an opportunity to own the offshore spillage, which I really like some of these offshore names that you like as well. So do you get aggressive on the short side, Kuppy, or do you just look for it [crosstalk 00:42:46] on the long side?

Harris K.: I don’t short stocks. I’ve had my head handed to me too many times. The way I’m thinking about this, and I’ve been early and that’s my own damn fault. But if you think of natural gas, what’s happened over the last few years, decade, really, but the last few years in particular is that you’ve had a lot of by-product natural gas from shale primary oil players. And this by-product gas has byproduct. No one cares what the cost is. They just need pipelines to get it out of the Permian or out of the bock or whatever. And so it’s just coming to market and it’s basically crowding out everyone else in the gas space. If you look at conventional gas production, it’s gone way down over the last decade. If you look at guys in the Marcellus are even slowing down, I mean you have Haynesville, but then you have these other basins where guys just stopped drilling years ago because they weren’t competitive. And you have this real crowding out.

What I’ve been looking at is the view that as primary shale guys, oil shale guys who have a nat gas byproduct, as they start slowing down, you’re going to see nat gas prices improve. And we’ve already seen this. It’s been nine months straight now where a US nat gas production’s been flat. That’s usually the first step towards rolling over. It’s flat because a bunch of other shale plays are declining. I mean, one of the things that’s funny about shale is that if you don’t keep drilling wells, you decline pretty fast.

So it’s going to solve itself as the shale guys cut off. I have a very large position in Antero Resources. It’s been one of the worst investments I’ve made in a very long time. But they’re fully hedged for the next two years, so I don’t really care what happens to the price of nat gas this year or next year. And by 2021, I think they’re the last man standing in terms of nat gas because most of the competitors are somewhat hedged this year and not hedged next year, and they’re all going to go broke. And when you go broke, you stop drilling. Antero is actually making money at these prices, mainly because of their hedge book. But I think it’s one of those ways you can play in nat gas and see what happens in a recovery, because I do think there’ll be a nat gas recovery. Any time anyone tells you that there’s too much of something, it’ll never go higher. As people keep telling me about nat gas, it’s probably about time for it to start going higher. [crosstalk 00:45:12].

Then again-

Mike Alkin: No, go ahead. Sorry.

Harris K.: Well, I was just going to say I’ve been wrong for a year and a half, so ignore me also.

Mike Alkin: Yeah. But you guys know from talking with me and to me about my view on nat gas from having done the work on it as it relates to the uranium sector, multibillion dollar capital allocation decisions, with respect to transitioning as they get out of coal and going towards nat gas power generation. You would think that to hear the utilities, think about it, nat gas stays below $2 and around that mark forever. And any time people, just you said, think a commodity is now a secular type investment, it just doesn’t work that way.

Harris K.: If you look at nat gas, just look at what is coming down the pipeline in terms of demand. You have all these petrochemical plants coming back to America. You have fertilizer, you have the switch from coal to nat gas for electricity. You have all these L&G, you have exports to Mexico. You just start adding up where the demand is and then you look at the supply and it’s like, “Hey guys, we’re supposed to be massively over supplied but we haven’t increased supply in nine months.” And the weather hasn’t really cooperated, which is partly why gas prices are down. It’s partly sentiment. Everyone thinks there’s too much gas. But when you look at it and you don’t look at it in terms of the average storage or the last five years, but you think of it differently and you think of it in terms of storage divided by usage, because usage has increased quite a lot, and if you start looking at it in a different metric rather than just base storage, nat gas right now is that some of the lowest levels it’s ever been in terms of storage. We have a bit more than last year, but usage is up also.

And so if you have any shock in the system, a cold winter, a really hot summer, whatever happens, I think you’d have some fireworks, particularly because demand keeps growing.

Mike Alkin: So one of the things when you make a living taking the other side of convention, in other words, when it’s called contrarian investing, a lot of the times you sit around and you say to yourself, “What are these people, stoned? What are they thinking about?” And when I think about stoned, I think, Kuppy, about, you have a website, adventuresincapitalism.com. And I went on there, and July 15th you posted something I thought was hysterical and really poignant.

Harris K.: Thanks.

Mike Alkin: And it was called Stoned. And you talked about the cannabis sector. And I’m just going to read a brief excerpt from it. It says, “You have the economics of growing celery with all the government regulation of an HMO, complete with the regulatory risk of manufacturing pharmaceuticals with the two-tier system of legal and illegal producers, where legal prices are dramatically more expensive with hundreds of entrants funded with billions in equity capital who don’t care about near term economics, all locked in a vicious price war focusing on gaining market share. If it sounds like an insane place to invest, that’s because it is, particularly as demand is stagnating. You’d have to be stoned out of your mind to want to own any of these companies.”

I don’t know the cannabis base at all, but share with investors what your thoughts are there.

Harris K.: I think you just summed it all up.

Mike Alkin: You want to drill down a little deeper or …

Harris K.: Yeah, sure. Look, the cannabis space, there’s going to be some huge winners. There’s going to be a lot of losers. I don’t think we’re at the part yet where we figure out who the winners and the losers are. Right now it’s just a giant land grab. What’s crazy, though, is that everyone’s throwing money at this land grab and no one can make money, and you need to eventually have some consolidations and real losers, and you need to figure out who’s going to be the winner. But everything’s priced as if they’re a winner right now, which makes no sense either.

The thing I’m cuing off, I have a very good friend in the cannabis industry who made an amazing amount of money as an early entrant, so he keeps giving me updates and he just keeps saying you wouldn’t believe how much supply there is. There’s so much inventory. No one knows what to do with it all. I mean it’s called weed for a reason. It just grows like a weed. And no one knows what to do with all this inventory. You look at Canada and it’s what, like 20 months of supply? Yet every major producers talking about fivefold increasing supply. And so with a lag of about a year, you got to build a greenhouse, plants and plants, you just have more and more supply and no one’s making money at this now. It’s going to get worse and it’s going to get worse, and a lot of these companies have debts. They’ve raised a lot of capital, but they’ve lit it all on fire. I guess the going joke around our office is cannabis stocks are getting smoked. Sorry, it’s not that good.

Mike Alkin: It sounds pretty good.

Chris MacIntosh: No, but I think it is. It’s similar to the shale where you’ve got to keep going. You’ve got keep running on that treadmill to keep ahead, which just keeps the equity capital coming in so that you can keep the lights on, but that you’re just running towards a closed door. And it’s similar to the shale, where these guys have to keep production up even though they know that they decline rates are significant, and even though they know that they’re actually losing money on every well at that drilling. There is no solution for a product that you’re producing at a loss. The only solution is to lower your capex and opex to the point where it is profitable, or for the price of that ultimate good to rise significantly enough for it to be profitable. That’s the only solution.

Harris K.: Chris, I’m going to interrupt you there. The product’s the shares, not the weed.

Chris MacIntosh: Yeah. In this instance. Well, I guess that brings us into the next thing. You mentioned that you don’t shorting and you know for a while that we tend to shy away from that as well. And so, it’s easier for me to look at stuff and say, “Well, what’s the secondary effect? What’s a second order event of pot stocks collapsing?” And I don’t really have one. I just know that I don’t want to be anywhere near that spice. I do think that coming out of it, I want to buy the snot out of the guys that do remain, because you’re going to have a whole lot of guys who just get wiped out and we’re going to have exactly what happened in the alt energy space in my humble estimation.

So you’re going to have probably 70%, 80% of these things blow away. You’ll have massive consolidation. Somebody, a bunch of companies will retain that market share, they will become the Coca-Colas of the industry. They’ll basically be branding marketing companies and they’ll have set up decent distribution chains and they’ll have managed the regulatory environment, and there’ll be the winners and nobody will give a shit and they’ll be printing money and there’ll be paying out strong dividends and still nobody’s going to give a shit. And that’s when I want to buy them.

But we’re a long ways off that. So in the interim, I don’t really know what to do with that other than just look at it and giggle a bit. But shale’s more interesting because the knock-on effect of shale is actually much more significant. Everybody got this linear assumption and that feeds into what you’re talking about, nattie gas. Everyone’s like, “No, we’re going to have plenty supply of nattie gas.” Well, okay. Where does nattie gas come from? Well, that’s a huge source of supply. And is it reasonable to think that that’s going to continue? I don’t think so. You don’t think so.

I mean, look, when you look at the production of shale, they have to just keep going faster. It’s not even just staying on the hamster treadmill, they have to go faster and faster. The drop off rate on some of these things is 70% in the first year, 40% in second year and 30 in year three. And also, let’s assume that all the company wants to do is just to maintain its year one production in years two, three and four. So if you’ve got, let’s just say, for shits and giggles, 10,000 wells drilled in first year all at once, then the company is going to end up with, say 10,000 barrels in end of year one. But to maintain production at the end of year one, they’re going to have to drill 7,000 wells, and then end of year two, 6,100 wells. And end of year three is going to be five, five and a half, something like that.

So, it’s just on top of what they’ve already drilled. You can’t fix the stuff. And so, it’s similar to the cannabis space, these guys are trying to grow market share, and in order to grow market share, they just blazing growing more weed, acquiring more acreage and so on and so forth on fundamentally broken economics. So it’s inevitable that it’s going to break. In cannabis, I don’t really know how to play that. I mean shorting’s a tough gig. But in shale, it’s like you can see when that narrative breaks and people go, “Oh, holy smokes, this stuff didn’t ever work. It never did. And it’s not going to work now.” Then nattie gas suddenly, there’s the potential that we have the same insane, linear extrapolations take place. But on the other side, where suddenly people go, “Oh my God, we’re never going to have enough natural gas.” And then what’s the price you’re going to pay for that? Or, “Oh shit, we really need good old fossil fuels, and offshore oil because it’s not coming from shale.”

And look again, there’s nobody left. There’s just literally nobody left in that space. So, that’s how we tend to look at identifying opportunities. And what it typically means is that you’re lowering your risk because you tend to be buying these companies, which have already been through bankruptcies. Plenty CEOs have already left, pink tickets have being handed out, all the debt holder got wiped out, equity holders all pissed, there’s very few of them left. And at the same time, oh, the company’s actually profitable.

So you’ve got these hugely capital-intensive businesses sitting out there, no one really gives a shit about them, there’s very few of them left, and so you can sit on those for quite a while without worrying about that short-termism in the market and what happens? Whereas with a put option, well, you’ve always got expiry, right? And you’ve got to keep rolling it. Perfect example, we’re all massive bulls on Tesla. We think Elon Musk’s the best thing since sliced bread, that’s bullshit of course. He’s a complete charlatan, but you can short that, but you gotta keep rolling those positions because he keeps pulling shit out of a hat. I mean, the latest one is going to wire our brains up with …

Mike Alkin: Let’s talk about that for a second. Kuppy, have you in your career ever seen anything the carnival parker that is Elon Musk and what he’s perpetrated on the capital markets?

Harris K.: It’s just amazing. I don’t get it. I haven’t gotten it. I’ve made a bunch of money actually just trading around it, but I just don’t get it. I mean, he’s a giant fraud. And he just makes stuff up. The regulators have abdicated any responsibility for doing their job, and I don’t really know who these retail guys are who buy it. At some point they have to realize that if you’re going to lose a couple hundred million dollars a quarter, probably going on a billion next quarter, it’s just not sustainable. I’m at a loss.

Chris MacIntosh: They’re the same people that bought housing in ’06, mate. They’re always there.

Harris K.: But a house is real. You can look at it, touch it. They must know this thing is fake.

Chris MacIntosh: Or the same guys that bought the dotcoms in the late ’90s, early 2000s.

Mike Alkin: The thing with me, though, that that blows me away here is, Chris, good point, the dotcoms, but eventually when page views slowed down, or when less eyeballs were there. When the numbers started to go, people started to bail. And here, I’ve never seen anything it where numbers be damned. You might have a day or so where it’s down a little bit, but then the narrative shifts to things that are nonsensical, to things that are going to require such capital investment that they’ll never come to fruition yet he’s able to change the narrative. And I’ve not seen anything like it. And realism be damned, right, whether or not it makes any sense.

How about going into the last quarter? Think about this. The stock’s sitting at around 170 and who knows where the margin calls are, but probably not too far where could financially collapse. Yet going, what, four, six weeks before the quarter ends, the leaked executive email to the website that is basically a promotional website for them. All of a sudden that leaked email about deliveries, you don’t think they knew they were dropping prices a rock and you don’t think they knew what those numbers were going to be? But he gets the stock up to 260, 270, which gives him more cover for when the shitty numbers come from a margin call perspective. That people don’t see through that, or the regulators don’t do something about that, to me is mind numbing.

Harris K.: Regulators gave up long ago.

Mike Alkin: Yeah.

Chris MacIntosh: I think so.

Mike Alkin: That’s the sad commentary on that.

Chris MacIntosh: I went to go and watch Spiderman with my son the other night. [inaudible 00:59:47] we go and watch Spiderman. So, I took him and a couple of his mates to watch Spiderman. I’m sitting there watching his thing, completely shit movie, but I guess I probably would have liked it when I was 14. Anyway. And they’re talking about Ironman right in the movie, and he’s now driving the story. They’re looking back on how wonderful he was and all this stuff, and everyone compares masks to Ironman, right. And I was like, you know what it is. The reason that my son, or when I was 14 were like that is we all want to hero. We all want fucking Ironman. He’s a cool dude. He’s just unbeatable. He can do all this stuff.

And people want someone like that. And Musk basically gives it to them, and these types of people exist in the world, to a certain extent on the really, really bad end of the spectrum they’re your Hitlers. Hitler came in at the time and he gave people what they wanted. They’d come out of World War 2, and they were paying reparations and basically life was pretty shitty. And the economy was tough based on a lot of those things that had taken place previously. And he gave them what they wanted, which is, “Hey, it’s not your fault and I’m going to make things better for you and everything else.” And he used all these narratives to get himself into that position and power.

Musk does a lot of that. He uses the climate change, global cooling, global warming, pick whatever the fuck you want narrative any time somebody attacks him, one, he flies around in his jet of course and lives in his six houses or whatever. And so he uses that narrative. He uses literally anything that’s taking place at that present time. He’s a master of, I think, identifying those sorts of opportunities and really going in and sucking the most juice out of them. And it’s interesting, because he’s not particularly eloquent. In fact, he’s awful. Who uses [crosstalk 01:02:18]-

Mike Alkin: I almost think that’s intentional.

Chris MacIntosh: Oh, I’m the geeky … I think that’s his play.

Mike Alkin: It’s intentional.

Chris MacIntosh: Yeah. Yeah. And he’s the geeky, awkward guy. And so people, as a consequence, they let him get away with things that don’t make any sense. When he stands up there and he talks about things, it could be in the medical space … There’s a great article, people can Google it, written by a neuroscientist, he says, “Look, I don’t know anything about Musk, but this is what I do know.” And he writes about this article. And you basically just rips him apart. He’s like, “This is complete rubbish. What he’s talking about doesn’t work, doesn’t make sense.” He just rips it apart and he’s just doing it purely from that medical perspective.

But the interesting thing is that doesn’t matter, because most people don’t really want the truth. And they’re not going to read that guy’s article, which is buried on page 50 of Google or something that. But they will read front page news about Elon Musk.

Mike Alkin: Well, Jack Nicholson invented that. You want the truth? You can’t handle the truth. [crosstalk 01:03:41].

Chris MacIntosh: What was it? They said truth is like poetry, and most people fucking hate poetry. And here we are.

Mike Alkin: Okay. Let’s shift gears for a second. So, Kuppy, you have Praetorian Capital, and I think I read somewhere in the first five years, every dollar invested on day one would have been worth $26 before fees. Not bad math. And you recently reopened it, and you do a lot of macro stuff, and the thing about macro, I think we were talking over the weekend, the three of us and Raoul Pal from Real Vision had put out a tweet in [Rebels 01:04:30]. He’s got an excellent website, and he said there are only three PMIs in the world, purchasing index, manufacturing index in the world that are above 50: India, Brazil in the US, all three are decelerating. 47 usually signals a recession. All PMIs are falling very fast currently, and a global recession is just a few months away. And they’ve spent the last couple of weeks doing a feature on that.

And so, how much for both of you, but Kuppy, how much does the macro play into it for you, and how do you factor that into your decision making and sectors you’re looking at and what are your overall macro thoughts in your thoughts on the market?

Harris K.: Well, the macro is everything, really. If the macros coming at you in the face, it doesn’t matter what’s going on. If you have a macro tailwind, some of the dumbest things you do usually get bailed out. I mean, the macro is the most important. You look at the macro first and you figure out how to play it. I actually spoke with Raoul as part of a series, I was speaking with him about shipping. And I think he’s spot on in terms of what’s happening, and it looks bad out there. It doesn’t guarantee you have a recession, but it doesn’t look very good. And in terms of how you play that, you want to be positioned with the macro at your back. So you want to be in sectors where things are getting better.

And just because the PMIs are rolling over doesn’t mean that there aren’t going to be winners. Shipping, like the Baltic Freight is that a multiyear highs right now. Trade wars are good for shipping. [inaudible 01:06:13] 2020 is good for shipping. You want to be in places where the wind’s at your back, you want to be at places where you think there’s going to be inflection. Just because US GDP or global GDP is rolling doesn’t mean there’s not going to be good places to play. And of course when the economy rolls over, guys can make a lot of money short, but shorting is very hard, and the most you can make is 100%. And buying puts is hard because you have to pay a lot for them. Usually when the right time to buy puts comes up, the guys selling you puts know about it. So they charge you a lot for those.

So I’d rather find things that are going to go up a lot. You’ve been pounding the table on uranium, and I think you’re probably right about that. It’s another situation where it doesn’t really matter what’s going to happen, to global GDP. If utility needs uranium, they just need uranium. They’re not going to shut down the plant because they’re not willing to pay up a dollar. So, you just need to be looking for places that are inflecting or tailwind and get out of the places where it’s a hurricane.

Mike Alkin: So how much in your portfolio, from a portfolio management perspective, where you don’t short, you don’t buy puts, do you use cash as your hedge?

Harris K.: Yeah. I use cash as my hedge. I own some Tesla puts. I broke my rule once and …

Mike Alkin: You can’t help yourself on that, right?

Harris K.: Yeah.

Mike Alkin: Yeah. Almost on American not to.

Harris K.: Yeah. And I got my little cannabis basket, but “little” is the keyword. But I own a lot of cash right now, I run a fund, we’re usually six to 12 positions, very concentrated positions. And the a good thing about how I set up my funds and my strategy is that if I sit in cash and I underperform the market, I don’t care, because most of the money is made those two or three shots each year, every two years we can do some really, really smart and take big positions. And the rest of the time, if it’s not completely brilliant that you can’t just draw on the back of a napkin, it’s probably not doing and you just wait for those setups. And yeah, I’m sitting with a lot of cash. I’m sitting with my Tesla puts, I have some longs and things I like and I’m waiting for the layups.

Mike Alkin: Well, as Buffet always say, investing is a great business. You could be a bat and never have to swing, right? [crosstalk 01:08:32].

Harris K.: That’s true.

Mike Alkin: Chris, how do you think about the macro? I know you’re a big macro guy, but when you’re thinking about portfolios you and Brad McFadden run, how do you guys think about the macro and how does that get incorporated into how you express the view in the portfolios?

Chris MacIntosh: I guess there’s two ways that we look at it. First is along that macro line, and we’re trying to figure out what’s going on. And most of the stuff is … What’s that old saying, a good economist can see what’s coming and a great economist can see the second order events of what’s coming. So, we almost always will look at what’s the second order of events, if you go back to shale for example. Well, you could look and then go, “Okay, what can short that?” That’s not the way that we prefer to do it. We to look at what has happened as a consequence of shale or as a consequence of the massive amount of shale oil has been brought on, offshore oil drilling for example, has absolutely collapsed. A lot of other sectors have absolutely collapsed because of the supply that’s been brought in and the nattie gas space. A lot of the players in there have been smashed. And so, those are more interesting to us to play that in from that side of things.

The other angle that we look at is typically we’ll trawl through and look for stuff that is absolutely hammered, and not really on an individual basis because you can always find an equity that’s been smashed. And it could be because the CEO ran off with the CFO’s wife and stole a billion dollars or God knows what. But when you find an entire sector that looks like that, then it’s like, aha, okay, this is interesting. And that could be anything. You might find that it’s literally buggy whips and its gone away and it’s going to be replaced by something else.

On the other hand, when you come across things like shipping for example, you sit there and you scratch your head and you go, “Hmm, okay. Even if we had a recession, even if we had a global depression, are we still going to ship goods? Yep. Probably.” And so you start looking at those and you factor that into your equations. And so we look at it that.

The other thing, coming back to Raoul’s thesis, if you will, he’s basically calling for a global recession. When I think about that and then when I think about what’s taken place in the certainly sense of GFC, and even prior to that, but especially so since the GFC, the central banks, they’ve had a chance to play with tools. They’ve played with their toys and post GFC, they basically have sat back and then clap themselves in the back and, “Shit. Guys, we fixed that. We came close.” And so, my estimation is that they already have tried those tools and they are going to use them even more so, really just because they don’t really have much else that they can do. And so from that perspective, I’m actually pretty reluctant. I’m not long, the spoos or the decks or anything that, but I also don’t want to be shorted because I don’t know what they’re going to do. Can they come out and just start buying up all of the ETFs? Sure. Why the fuck not? They’ve been buying up the bond, the European bond market’s completely broken because ECB basically controls that.

So, I’m reluctant to do that. But then when I think through how does that end? I kind of think it feels it ends with a stagflation. People talk about how there’s never going to be inflation. And I shared with you guys the other day when we were chatting, a post from Kevin [Muer 01:12:45] where he was giggling and laughing and saying, “Well, he has two covers and one’s from Barons, and the other …” I can’t remember what the other financial publication was. The one was all in is inflation dead and the other one was negative interest rates, the spiral, we will never get out of or something of that nature.

Anyway, when most people think about inflation, they think about demand led inflation, which is what happens when an economy booms. And that’s because that’s in the more recent history. That’s what we’ve experienced. And I think that this time the inflationary pressures can actually just come from rising costs and actual shortage of goods. When you think about uranium, Mike, is that an inflation, deflation? You go no, it doesn’t matter. There’s a supply deficit coming. It doesn’t matter. The only way it gets fixed … And when you look at a lot of [crosstalk 01:13:53]-

Mike Alkin: Inflation in the commodity comes because of a shortage in the commodity.

Chris MacIntosh: Absolutely, absolutely. So in that environment, does it really matter what the Fed do? It does, insofar as, it can … Well, firstly, if we go back to uranium, the price has to rise for the miners to actually bring on supply, which the utilities have to have. Otherwise they turn the lights out and then the business goes away. And then once 11% and 12% of global energy supply chains off, we’re all fucked. And then it’s not going to happen. So the alternative’s, okay, the price is going to go up.

Now, in that environment, if the fed came out and started pumping more liquidity into the markets, would they have benefit? Yeah, probably, on a percentage basis. It probably benefited more insofar as there’s a potential that more capital goes into those equities as opposed to less. But they can’t change what’s going to happen because of actual physical supply-demand deficit. And so what people forget is that you can have easily a declining economic growth and you can still have shortages. I mean, shit, all you need to do is look at Venezuela or Zimbabwe or Yugoslavia in ’03. There’s currently this interesting narrative that, oh, we can have recession and it’s a popular one. And probably, yeah, fine. But to a certain extent, I don’t really care.

So if there’s a recession, people go, oh, well, we’re not going to need any copper. Copper is going to go off. And I’m like, well, hang on one second, dig a bit deeper. Right? And so, maybe that’s the case but if you dig down and you see what the supply-demand structure is and then you go back and you can have a look at previous recessions, for example, that’s not always the case.

And the other thing, there’s an interesting thing that takes place, and it’s really taken place in the energy space. There’s this massive narrative where part of its climate change and there’s all sorts of different puzzle pieces essentially. But essentially you’ve got people saying, okay, we’re not going to really use fossil fuels going forward and, and they’ll pick a date. It’s going to be 2030 for ICE vehicles, and after that we’re going to get rid of this and get rid of that. And then you go, and you say, that’s the case of oil and you break down an oil barrel and you realize that about 20% of its gasoline. I think that there’s a whole lot of stuff that goes into which, it got nothing to do with that. And those industries are not going away. So then you realize that all oil is not going away. That’s one thing.

And there’s the other narrative that, oh, we’ve got wind, we’ve got solar and we’ve got all these alternative energies, they’re getting better and better, and yes, they are getting better and better and they are making up more of a global energy pie. They are taking up a greater percentage of that global energy pie. But when we have new energy sources, when man finds new energy sources, an interesting thing happens. We find ways to use it. So the pie grows, and a perfect example is coal. Everyone was like oh, coal is going to go away and you’re not going to use coal and dah, dah, dah, dah, dah. We’re still using coal.

Mike Alkin: Well, as a percentage of the energy mix, it will go down. But on an absolute basis, as energy demand grows, coal’s going to stay flat for the next period of years. Right?

Chris MacIntosh: Yep.

Mike Alkin: I mean it’s not going anywhere.

Chris MacIntosh: Well, this happened with wood. I think it was in the 18th century, we were burning wood, chopping down trees for energy. And then we found coal, and it was like bloody hell, this stuff’s amazing. This is ridiculous. It was so much better than wood. But guess what happened? For the next 80 years, wood consumption actually grew. It actually grew. And the reason is that we just found more uses for the energy. Suddenly we had the steam engine came along and all these other things.

So when you come back to the situation that we’ve got today, there’s a very, very strong narrative. We’re not going to utilize any of this. And we’re not going to use it to the extent that we know we should. And it’s just wrong. I think it’s Amara’s law, which is we tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run, and then we underestimate the effect in the long run. And that’s exactly what I think it’s taking place, and that lends itself to enormous opportunity in pretty much everything that we’ve been talking about today.

Mike Alkin: Yeah. Let’s go back to what you said earlier about copper, and we’re not singling out copper. I think it’s a good example for what I’m going to ask you, is people see recession, in today’s investing environment, and I’ve seen it change a lot over the 25 years, and it seems it’s much more of a ready, fire, aim market than it is a ready, aim, fire market. It’s shoot first, ask questions later. And so, from a portfolio management standpoint and you too, Kuppy, when you see things that you think are not going to happen. So you take that second level of thinking, because so much of this market moves on headlines and it moves on first level thinking, versus what does that second derivative of this?

How do you guys, and timing is always tricky, but let’s say you see something that where [inaudible 01:20:12] say, well wait a second and that’s not going to happen, but money flows are coming out of a sector. How do you, and this is much more of an art than science, how do you guys think about that before deploying capital into a sector where the first level of thinking is going to sell it off, but you know that ultimately it’s not going to play out that way. So how do you guys think about that from capital deployment standpoint?

Chris MacIntosh: I think Kuppy and I do quite different things. I’ll shoot with we go about it and then you can follow up, Kuppy.

Firstly, part of this is psychological, bending your own mind. I’ll take a position in stuff largely because if I’m not involved, I just tend to be lazy, I tend to not pay attention to the extent that I should. And so if I’m involved, then I’m involved. And it’s, again, it’s a psychological thing. It could be a few hundred bucks. It could be absolutely nothing, but I’ve got it in my portfolio, it’s sitting there, and it’s on my watch list and so I’m going to pay more attention to it. So that’s one thing that I do. And that’s really just, in order for me, because here’s the risk for me, the risk is that I get lazy, I get busy with other things. We’ve all got busy lives, we’ve got a lot of things that we’re looking at. And then I wake up two years later and I’m like, “Jesus Christ, I just missed the 300% move. And I’m damn it. I saw it. What the frig is wrong with you, Chris?”

And I’ve done that before. So I’m trying to check myself from doing that. I’ll take a very, very small position just so that I’m in play, if you will. And then, we’re not that concentrated, so we’ll take a sector for example that we like, and across that sector then we’ll say, “Okay, firstly we want to know the ability to stay in the game. So we’re going to look for example, for equities that don’t have a lot of debt, that are cashflow positive, that basically, they’re not going to go away. And they may not get us a 5x return or something like that, but these things are solid, they’re in the right space. Sure, they might go down 20%, 30% on a broad market move or the narrative is just really shitty for the particular sector, we’re okay with that because we know that they’re not going to go away. We’re not looking at a Tesla, we’re not looking at an Uber or something that just literally burns money and is heavily reliant upon capital volume markets in order to stay alive.

So, we’ll put some capital into those, and then we’ll structure a portion into much more risky plays so that our overall positioning, we could lose maybe 25% of that positioning in that sector. And it doesn’t really matter, because when they really move, they move and then you’re up three, four, five, 10, depending on what it is that you’re buying times. So that’s how we will look at it. And then each sector that we get into, often that’s maybe 5% as a waiting. That’s a full position for me on a sector. So, across a portfolio, if I cock up, or I could have a sector that takes longer to turn around and I’d anticipated or whatever it is, but it’s not going to kill me. And so it’s like I’ve got a lot of different irons in the fire and they’re all structurally sound. And it just sit there and wait for them to pop, and then take money off the table as that occurs.

So that’s how we manage Glenorchy Capital, and largely, we talk about the research side, but I know, Kuppy, you do much, much more concentrated stuff. So you shoot.

Harris K.: Sure. I guess, to start with, I agree 100% with what you said about having a position. Nothing focuses your mind like a few thousand shares in your balance sheet, and you guys stare at it every morning when you have your position report and you go, “What the hell is it? Why do I have this thing? Oh, I have to go read those filings now.” It makes you do the work. So I run a super concentrated portfolio, which means that you don’t have much room for mistakes. To start with, a balance sheet is the most important to me. I want something that has termed out debt, preferably no debt. I want something that’s going to make it through the cycle. I’m usually looking at stuff at inflection point and my experience as shown by nat gas is that sometimes they don’t inflect. Sometimes something that’s bad just keeps getting worse.

And so you need to make sure that you can see it through the cycle. In terms of Antaro, they have termed out debt, they have hedges in place, they own assets, they’re up their midstream company. It has the best balance sheet of anyone in the sector. They’ll make it through to the other side. From there, timing is critical and there is no a great way to say when it is to buy. What I have found, though, is that you never get the exact low tick. If you can get close enough, remember if it’s down 90% or 95%, you might have to pay up 10% so you’re coming into a down 89 instead of 90, it doesn’t really matter if you’re right.

And what I’ve found is that these things usually make a bottom, and there’s so much exhaustion, frustration, and if you look at something that just had its little crisis, you have a lot of people falling and a lot of guys trying to get the bottom, the Seeking Alpha guys are writing articles about how cheap it is. And then just slowly over time, and I’m saying time in terms of multiple years, people lose focus and lose attention, analysts get deployed to other sectors, trading volume goes down, you’re left with just the diehards that believe in it. look at Greece for instance, where I own the Greek ETF. And I didn’t get the low tick. I went there two years ago now poked around, told myself it’s not ready yet because they didn’t have a catalyst. And I don’t want to tie up my capital doing nothing. I want to make sure I have a catalyst that gives you escape velocity and can change the story. Just because it’s cheap doesn’t mean anything.

And so I was waiting for my catalyst in Greece. And it was obvious when they had an election that you had your change, and 10 years after the Greek crisis, they’ve had mini crises that are all self-inflicted and they had an election, the right guys won, and the day they called the early election was my day to buy because I knew that the story had changed, and yes, I had to pay up 10% that day and I was about 20% off the lows, but didn’t really matter because now I knew that the wind is at my back. Previously, you didn’t know what they were going to do in Greece. They could have still made a mess of everything. Once the wind’s at your back, you can go and think about it, who follows Greece anymore? No one notices, no one cares. They called the election and the Greek ETF, it does about a nickel a day. Just every day it goes up as people start reeducating themselves about Greece. Now I’m up almost 20% on this investment even though I had to pay up 10% to get in. And that’s in about two months.

The point is you wait for some obvious catalysts. In the case of shipping, I was able to watch shipping rates start to recover, but no one was paying attention. Everyone forgot about it. So yeah, I didn’t get the low tick, but I got good enough that I’m happy. And that’s the thing, I think being a masochist and saying, “I’m going to get the low and I’m going to buy every tick down.” Yeah, you’ll eventually get the low, but you might’ve started, you’re averaging down, 50%, 100% too high.

Mike Alkin: Yeah. Yeah. All right. That’s, no, that’s good. All right guys, any parting words?

Harris K.: Being a contrarian is hard. The question I always have amongst my friends and things we always debate is, because we’re all contrarians, which means the danger is when a bunch of my friends say, “Kuppy, you’re just wrong about that.” And I go, “No, no, no. Everyone always tells me I’m wrong, so I’m right.” And sometimes you’re just wrong. I think the most dangerous thing as a contrarian is when all your contrarian friends say you’re wrong, and you still go, “Nah, I’m probably right.” And sometimes you really are just wrong. If I had that skill to find that one out of five times that I really am wrong, I’d have a lot more money today. And I think that’s the hardest. It’s so easy to be a contrarian. It’s very hard to notice when being a contrarian isn’t ready yet. It’s my parting wisdom.

Mike Alkin: So true. Mac?