Editor’s note: The markets are selling off hard today amid growing fears of a recession. But it’s critical not to let fear drive your investment decisions. With this in mind, we’re revisiting a timeless lesson on how to take emotions out of your investing strategy…

Famous economist Daniel Kahneman once conducted an experiment on his students…

A student would flip a coin. If it landed tails-up, the student would lose $10.

Kahneman then asked his students how much they’d need to win on a heads-up flip to compensate for the risk. The typical answer was over $20—more than twice the amount they risked losing.

In other words, only a promise of a much larger reward could overcome the fear of losing money.

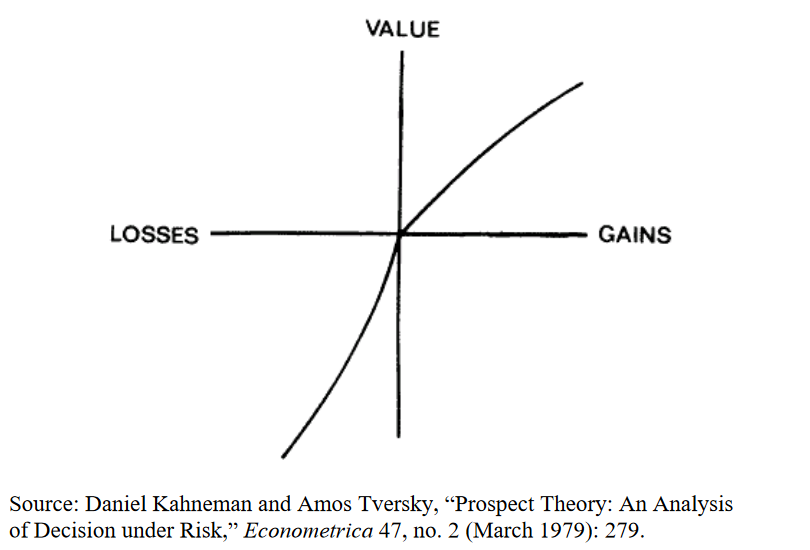

The experiment showed the Prospect Theory in action—for which Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2002… Put simply, this theory states that our hatred of losing is twice as powerful as our love of winning.

You can see this concept illustrated on the chart below.

Investors pay more attention to losses than to gains

Kahneman died on March 27, 2024 at the age of 90… But investors will continue to benefit from his insights for generations…

Today, we’ll examine how our biases impact our investment decisions—and hurt our returns…

And we’ll share a simple strategy to remove bias from your investing.

These biases are hurting your market returns

As Kahneman’s experiment above shows, fear of loss can be a powerful motivator.

Put simply, our loss aversion bias means we’re most reluctant to buy when the market is falling. (Ironically, that’s usually when you can find the best bargains.)

It also means we’re more eager to buy in when the market rallies. This tendency to “chase performance” is a major reason the market often overshoots—both on the downside and the upside.

At its worst, the fear of losing money can keep us out of the market altogether…

For example, millennials are notably averse to the market: Just 30% of millennials are invested in the stock market, vs. 51% of baby boomers. Many analysts believe fear is a motivating factor for millennials to stay on the sidelines, as the generation witnessed everything from the dot-com bust to the Great Recession to the COVID selloff.

It doesn’t matter that the market has returned more than 550% since the depths of the Great Recession (and around 100% since the COVID trough four years ago)—it’s still not enough to overcome their loss aversion.

Another bias Kahneman wrote about is hindsight bias. (While Kahneman’s student Baruch Fischhoff was the first to study this field of behavioral economics, Fischhoff credited Kahneman as one of his inspirations for the work.)

Also called “I-knew-it-all-along bias,” this theory suggests that people tend to overestimate their ability to predict events in hindsight.

Here’s an example:

In the late 2000s, researchers at Bond University conducted a study of venture entrepreneurs whose startup businesses had failed.

The researchers hypothesized that failed entrepreneurs would look back at their experience and say they “knew all along” their businesses would go wrong—despite their previous optimism.

The results supported the hypothesis…

Before their ventures failed, 77.3% of entrepreneurs believed their startup would grow into a successful business… But, after their startups failed, only 58.8% claimed they’d initially believed their business would be a success.

In other words, they judged their past decisions based on information they didn’t have at the time.

This is normal human behavior. We tend to look at past events as if we could have easily predicted them. Put simply, we overestimate our own wisdom.

This bias can be particularly costly in finance… It can lead to investors being overly confident about where the market is headed—once again leading to overleveraging (and setting ourselves up for major losses)… or waiting on the sidelines for too long (and missing out on the best gains).

Put simply, overcoming cognitive biases in investing is critical…

Thankfully, there’s one way to take these biases out of the equation.

A simple strategy to eliminate investing biases

Dollar-cost averaging (DCA) is the simplest way to put your investments on autopilot… minimizing the guesswork—and emotion-driven investing choices.

Simply put, dollar-cost averaging involves investing a set amount of money on a predetermined schedule, regardless of the asset’s price. If you have a 401(k), you’re already implementing this strategy: You automatically invest a certain percentage of each paycheck, rain or shine.

One of DCA’s biggest benefits is that it makes the inevitable market fluctuations work in your favor… by lowering the average price you pay for your position.

Because you automatically buy more shares when the market is low and fewer when it’s high, your average cost per share will balance out market fluctuations… eliminating the need to guess where the market will go next.

Put simply, it lets you avoid investing too much near a market peak… and scoop up more shares at bargain prices.

The bottom line: Because DCA puts your investing on a schedule, it takes cognitive biases out of the equation… allowing you to build portfolio positions across all markets—without overpaying or underinvesting.

For more actionable insights into how to profit in any market conditions, join WSU Premium.