“If you ever decide to trade futures, you’d better be prepared to take physical delivery.”

This was one of the first lessons I learned in my MBA Futures and Forwards class.

A futures contract, if you’re not familiar, is a standardized financial instrument designed to offset (or assume) the risk of a price change in an asset over time.

These contracts originated in the commodity market. Sellers (or hedgers) typically produce the commodity, or use it as a crucial input in their business. They want to be protected from price fluctuations, since commodity prices are highly volatile. And thanks to the futures market, they can create such protection months, and even years, in advance.

Speculators take the opposite side of a futures contract. They’re paid for taking on the price risk that hedgers want to avoid.

The hedger wants to ensure the price for his crop doesn’t drop, or that the price of his raw materials doesn’t rise… while the speculator wants to make money. This is why futures trades don’t typically end in the physical delivery of the commodity.

Instead, trades are rolled over into longer-term contracts, and the price differentials are “offset,” or settled between the buyers and sellers in cash.

In these cases, no physical goods change hands. The corn, wheat, oil, etc. gets to stay in storage.

But if a contract is allowed to expire, it will have to be settled.

This can be done either in cash… or via a physical delivery, depending on the market.

At this point, a buyer might have no choice but to take delivery… pick up the goods at the warehouse or other storage facility, and pay the full value.

My professor illustrated this concept with a photo of a mountain of wheat. “Imagine this in your backyard,” he said.

(One futures wheat contract equals 5,000 bushels—136.1 metric tons, or nearly 300,000 pounds… way too much to fit in a typical New York backyard.)

Today, he could’ve illustrated this point with a picture of 1,000 oil barrels… or an oil tanker.

Today’s $17-per-barrel oil price is the victim of a near-perfect storm—a combination of widely excessive supply and contracting demand. Both parts of this equation are hard to predict in these market conditions… and it’s been especially true for the supply side, with major oil producers still pumping way too much for this economy.

Similar to wheat, each futures contract amounts to a lot of oil… 1,000 barrels to be exact.

It costs money to store commodities. And there must be room for storage. At contract expiration, these constraints can become an issue…

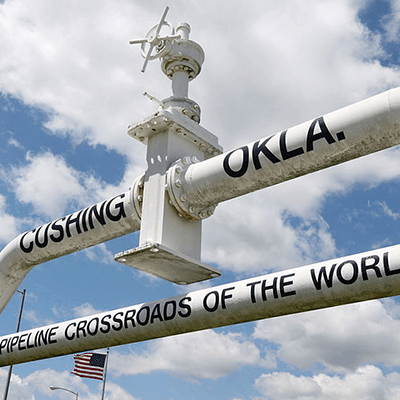

On Monday, the entire world learned that Cushing, OK—the largest oil-storage tank farm in the world and the main storage facility for West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude—is out of space.

Its storage facilities are either full… or spoken for.

I’ve been thinking about my professor’s words as I ponder the oil price crash… and the need to store excess oil. Our closed-down economies can no longer consume as much as they used to. We don’t fly and barely drive… and many nonessential factories are closed. There’s a real possibility that we run out of storage.

As you can imagine, as supply vastly exceeds demand and storage is getting full, oil prices come under pressure.

That’s what happened on Monday… With no more available storage at Cushing, the May oil futures contract plunged below zero for the first time ever.

Many futures contracts expire on the third Friday of each month—but there’s no set rule for expiration. The May 2020 contract for West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude was set to expire this Tuesday and had to be either closed or urgently rolled over on Monday… As a result, it closed at -$37.63 on Monday—a one-day decline of around $55 per barrel.

The contract expiration resulted in a flurry of selling…

The negative futures contract price essentially means traders are willing to pay $37.63 per barrel for someone to take the May contract off their hands… or to accept delivery rather than keep the oil in storage units (which are getting full and also cost money)…

The oil glut is real. As the producers keep pumping, they’ll keep running out of storage places.

All of this together results in dramatic oil price declines.

This is why I’m concerned about the energy market and energy company dividends.

Oil is the main product of the energy majors—long considered among the most reliable dividend payers on earth.

I’m afraid that’s no longer the case.

Tomorrow, I’ll tell you why this week’s wild action in oil is important for you… especially if you’re an income investor.

Editor’s note: In last week’s issue of The Dollar Stock Club, Harris “Kuppy” Kupperman—one of Frank’s most popular Wall Street Unplugged guests—recommended his favorite play on the oil storage crisis. He calls this trade “one of the best I’ve seen in my entire career.”

The Dollar Stock Club members got Kuppy’s pick for $1. Find out how you can, too.