We’re entering a unique place in economic history… one we haven’t witnessed since the 1940s.

In an effort to ward off deflation, the Fed has pushed bond yields to record lows—making these not only poor investments, but also risky ones.

Low bond yields are here to stay, but the Fed has inadvertently gifted us with a much better alternative for our money…

Before I get to that, it’s important to understand the deflationary landscape we’re facing today, and how we got here…

To stop runaway inflation in the early 1980s, the Fed pushed interest rates to 20%. Bond yields soared above 15%.

But as inflation trended lower and lower… so, too, did bond yields.

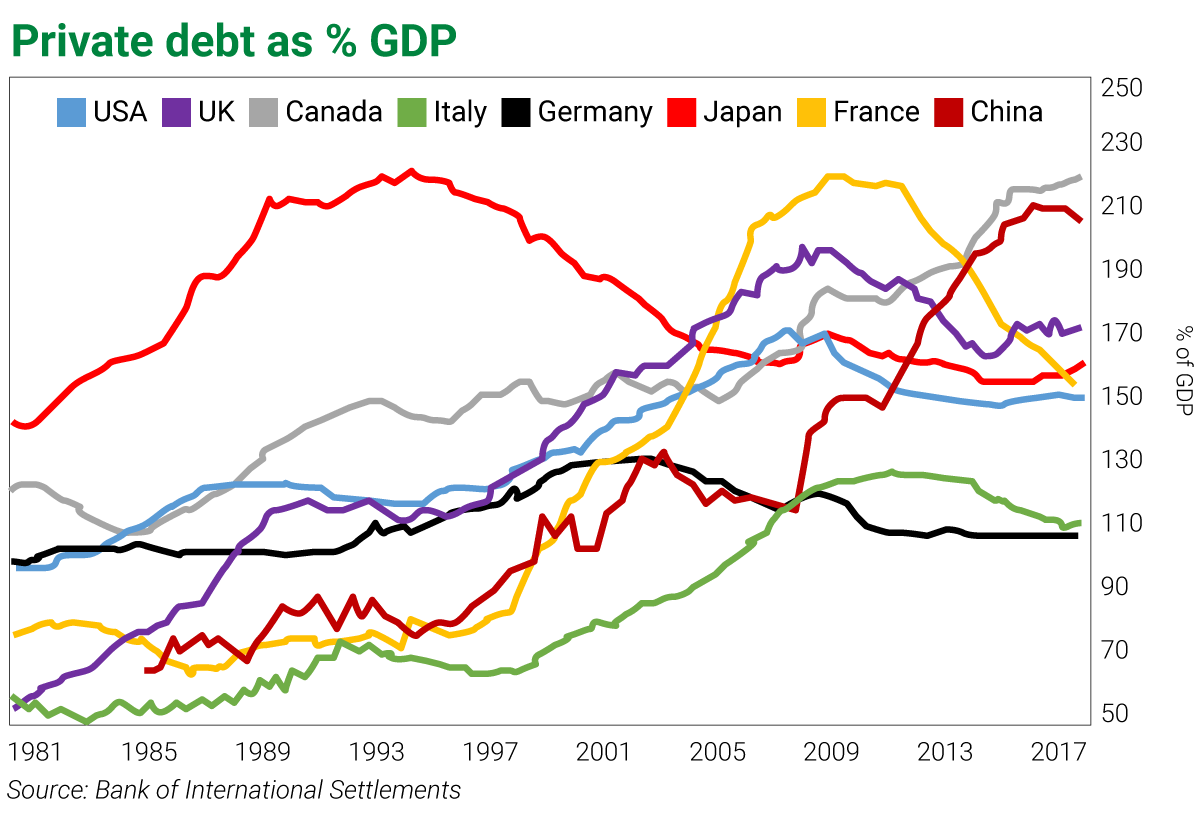

Lower interest rates in the ’80s kicked off a worldwide, ongoing borrowing binge among businesses and consumers… sending private sector debt to dangerous new heights.

A healthy level of debt is 100% or less of GDP. If it exceeds 150% of GDP, the alarm bells should be sounding…

When debt overwhelms the economy, debt service costs crowd out investors. Businesses and consumers use their resources to pay the loan principal and interest, leaving very little fuel for the economy to grow.

The borrowing cycle coincided with persistent inflation, peaking with the 2008 financial crisis.

But the debt repayment cycle is now exerting deflationary pressure.

If left unchecked, deflation could send the economy into a downward spiral. During the Great Depression, it caused the economy to shrink by 50%.

Like the Federal Reserve, central bankers all around the world now understand the dangers of deflation. They’ve learned to do whatever is necessary to avoid another deflationary spiral.

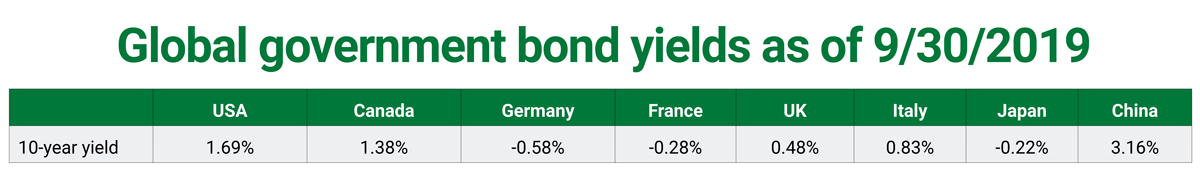

They’ve pushed interest rates to near zero. Bond yields, as you can see below, have followed suit, plunging to record lows.

This isn’t a temporary condition. Bond yields will remain extremely low for many years… probably decades.

That means bonds have become risky investments. If interest rates rise, you incur a capital loss on the bonds. The market risk is asymmetrical to the downside. For example… if you buy a 10-year bond earning 1.5% per year, and the market yield rises to 3%, your capital loss is almost 13%.

You can’t afford to buy bonds. To get stable income and returns, you’ll have to rely on something else…

Although the Fed has removed bond investments from the menu, it’s making stocks more reliably profitable. The Fed will support the economy and stock market with abundant liquidity… assuring steady gains and income from stocks.

Accept what the Fed has given.

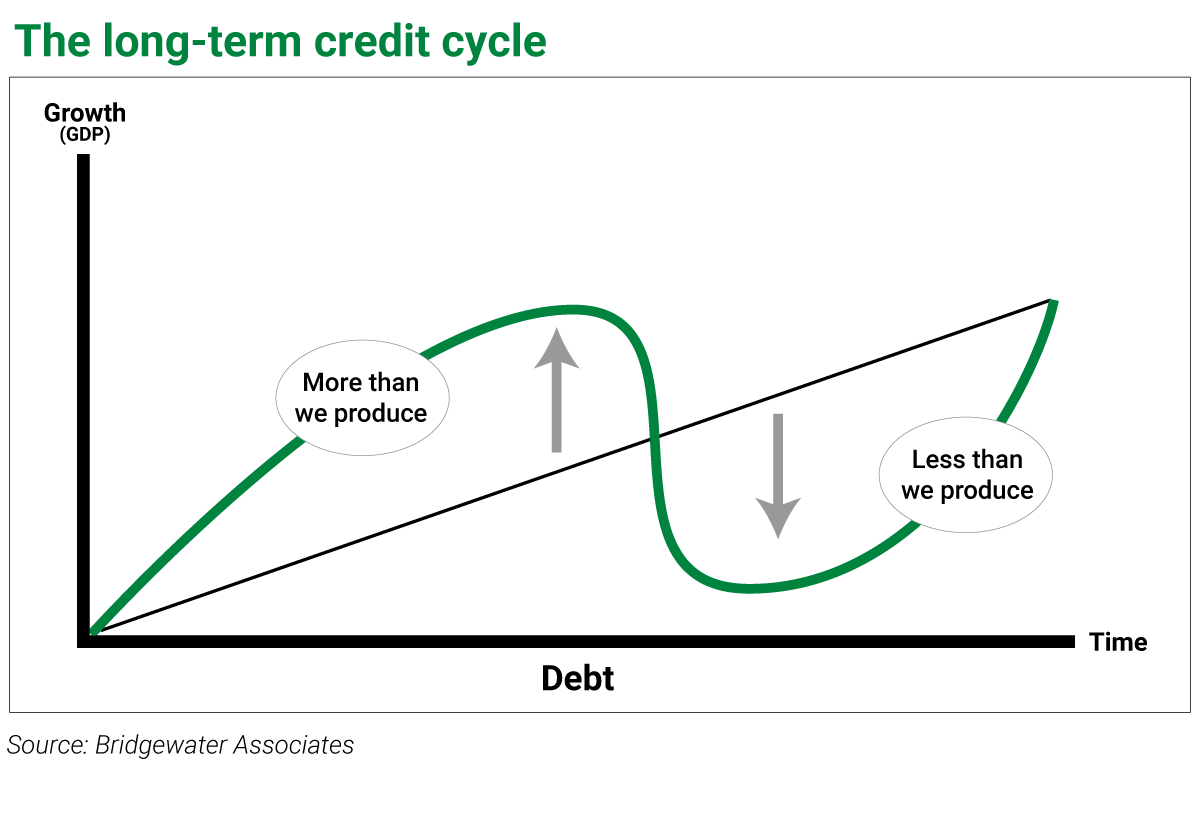

It’s keeping rates low. Not because it wants to… but because it has to. To understand why, let’s take a look at the long-term credit cycle.

How the debt/credit cycle works

In the expansion phase of the long-term credit cycle, borrowing enables the spending of future income. Faster spending puts upward pressure on prices… aka inflation.

Conversely, in the contraction phase, debt repayment is the payment of prior spending. Repayment results in reduced spending. It puts downward pressure on prices, aka deflation.

This deflationary debt repayment cycle is where the economy is right now… and where it will be for decades.

This deleveraging cycle will continue until the private debt burden shrinks substantially… perhaps to half of the peak level. The private sector won’t literally pay down the debt. Instead, it will restrain new borrowing. Debt will increase at a slower pace than GDP.

Eventually, the economy outgrows the debt. During that time, the Fed must keep interest rates as low as possible, boosting GDP growth and easing the way for debt repayment.

Using conservative estimates for growth, it could take 25 MORE years for the economy to outgrow the debt burden. For example, if nominal GDP grows 4% per year and debt by 2% (of GDP), it will take 25 years to get U.S. private-sector debt below 100% of GDP.

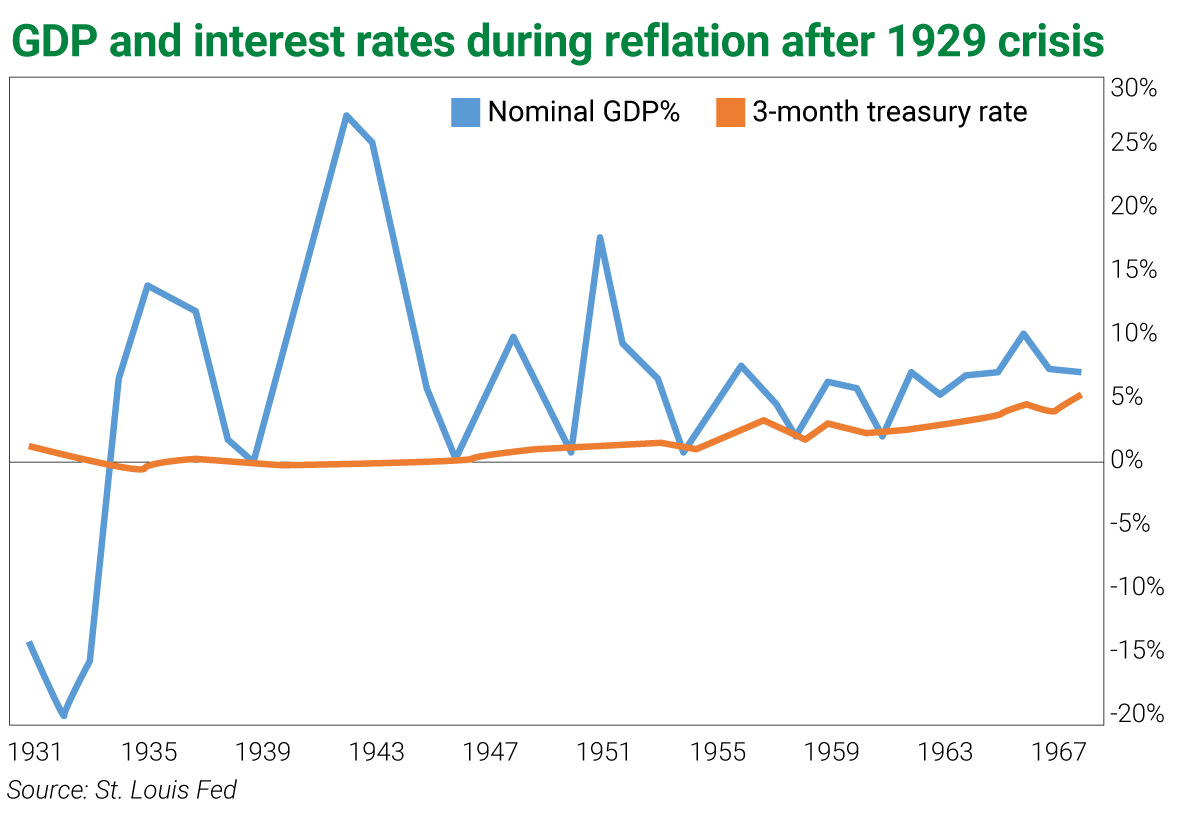

In the age of the Federal Reserve, which started in 1914, the U.S. has experienced only one other long-term credit cycle, following the 1929 crash. After the crash, the Fed had to suppress interest rates for 27 years.

Specifically, the Fed kept interest rates below 2% until 1956. During that time, the economy experienced two big wars and many years of double-digit GDP growth.

As you can see in the chart below, between 1942–1943, GDP growth exceeded 20%. Nonetheless, the Fed kept rates near zero, typically at 1%. (The Fed didn’t publish Fed Funds Rate data back then, so we use the 3-month T-bill rate as a proxy for short-term interest rates.)

Despite a series of war-related inflation shocks, the deleveraging process always forced inflation back down… to lows of 0% in 1944, -2.9% in 1949, and -0.6% in 1956.

The current deleveraging cycle is very similar to what occurred in the 1940s. Like that extended cycle of low rates, the current cycle will take a generation to play out. It started in 2008. After 11 years, debt/GDP is still at 150%, just 20% below the 2008 peak.

In 2018, the Fed made the mistake that probably extended the deleveraging cycle. It raised rates too much and too soon. The December 2018 rate hike to 2.5% slowed nominal GDP growth from 5% to 4% per year. Inflation fell to around 1.5%. Bond yields tumbled… even as the Fed raised interest rates… because the Fed was magnifying the deflationary pressure already present in the economy. To no one’s surprise, inflation has declined from slightly elevated levels in 2018.

Now the Fed is lowering rates to correct the mistake. It’s hard to know where the Fed Funds rate will settle down. It will probably settle between 1–1.75% for the next two decades… And it could drop to zero, temporarily, if the global economy goes into recession.

Low interest rates and low bond yields are here to stay.

But don’t worry about the lack of bond investments. You can find an abundance of stable, high-yielding blue-chip companies. Low interest rates and abundant liquidity have helped to lift these stocks, keeping them on a stable path of appreciation.

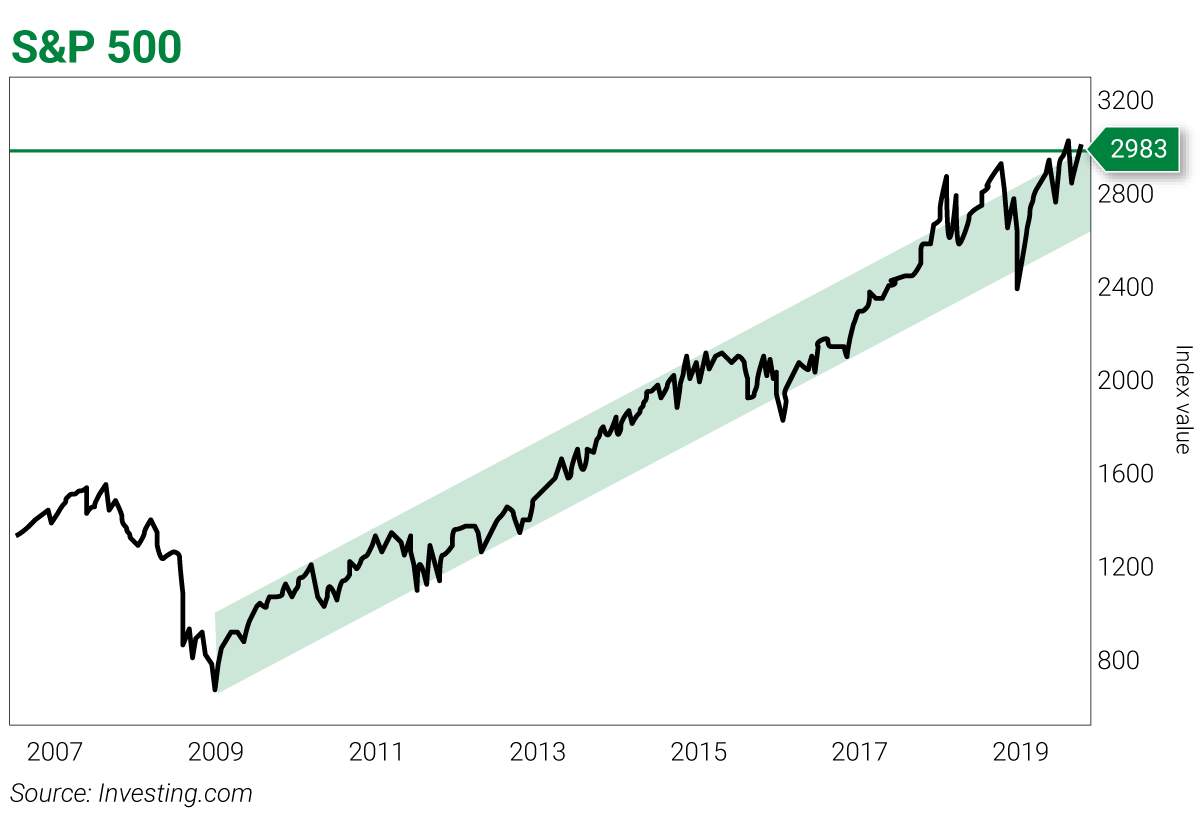

The chart below shows how the Fed’s low-rate regime since 2009 has largely tamed S&P 500 volatility. The stock index is rising steadily… staying in a well-defined channel most of the time.

In place of bonds, you can make blue-chip stocks the foundation of your portfolio.

Do your homework. Search for high-dividend, large-cap stocks with steady earnings and dividend growth. Buy a widely diversified portfolio of these high-yielding stocks. It will pay off handsomely!

All the best,

![[signature]](https://www.curzioresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/SKoomar-sig-1.png)

Steve Koomar

Editor, Vigilante Investor

Editor’s note: Steve Koomar is a former derivative trader at Goldman Sachs, editor of Vigilante Investor, and our newest Curzio contributing editor. The breadth of Steve’s knowledge continues to amaze us… If you missed it, be sure to read his commentary on the Saudi oilfield attack… and his favorite way to play rising oil prices.