During my second year of business school, my professor presented my class with a game…

The goal was to earn the most money trading the markets by the end of the semester.

As competitive analysts-in-training, we attacked the assignment with relish.

It was January 2000… the peak of the dot-com bubble. The bull market had been raging for several years and most of my classmates (as well as most of Wall Street) assumed tech would continue to rally.

But my first job on Wall Street had taught me to go against the grain… look past recent trends… and focus on valuation instead.

It was clear to me that tech stocks were dramatically overvalued… and I believed the Nasdaq would fall within the first few months of 2000.

Here was my rationale:

Investors had been pouring money into high-flying tech stocks—a motley crew of unprofitable, internet-adjacent companies.

More traditional tech was also flying high. In fact, following the dot-com bubble bust, it took more than 10 years for software companies like Microsoft and Oracle to exceed their dot-com levels. And hardware giants Intel and Cisco still trade below their 2000 peaks (even counting dividends).

Then came the Y2K panic… and tech spending further accelerated as the world looked for a patch to this major, potentially civilization-destroying bug.

The Nasdaq rallied harder… and by the end of 1999, it had doubled year over year.

But as we rang in the New Millennium, it became clear the apocalypse wasn’t imminent… And investors no longer had an obvious reason to continue pouring into hardware and software.

It wasn’t long before the tech-driven rally started unraveling… And at the end of the semester, I won the game.

Two years after the turn of the millennium, the market was still down by 27%… and the tech-heavy Nasdaq was down by more than 50% vs. March 1999 (and 80% off its highs).

The dot-com bust… the Y2K panic… and the market action that followed contain 2 important lessons for today:

1. Over time, markets tend to move higher

Even bear market selloffs don’t last forever. If you have a long enough time horizon (or don’t live off the market gains)… buying during large declines can pay off big. Going against the grain and buying on market weakness is one of the most profitable long-term strategies.

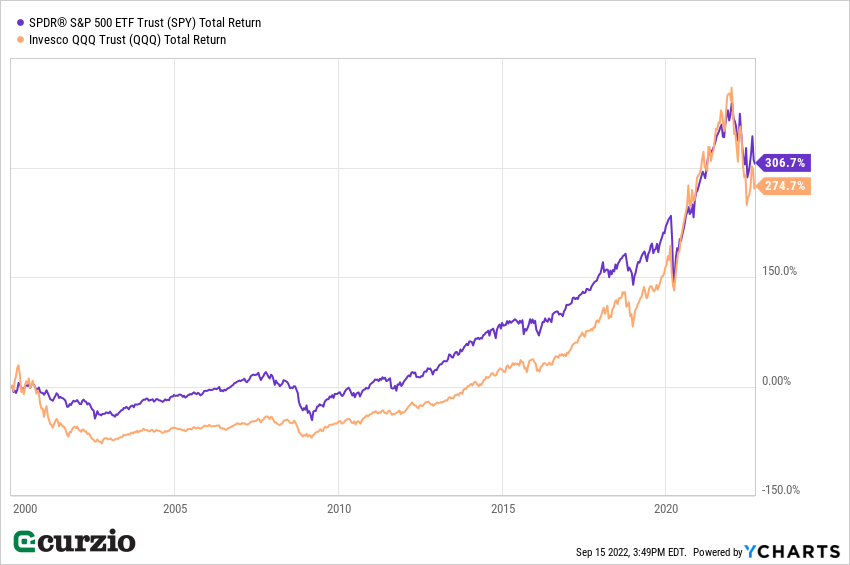

More than 22 years after the Y2K scare (and after three more vicious bear markets), we’re up multifold on both the S&P and the Nasdaq (as you can see below). And buying in the middle of any of the past selloffs rather than on top of the rallies would have improved your returns dramatically.

2. When the market sells off, it pays to own insurance

When the markets are down, there’s rarely a place to hide.

For example, even though small caps outperformed both the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq from 1999 to 2001, at some point during that bear market, small caps lost more than 40%.

And in the bear market of 2022, bonds—a traditional safe haven—have underperformed stocks by a wide margin.

It pays to stay alert in difficult or changing markets—and to always be prepared for a selloff.

One of the best ways to hedge is with put options. These act as “insurance policies” for a market downturn. When the markets fall and investors panic, these investments soar…

Over and over again, I’ve seen put options return hundreds—even thousands—of percent gains in a selloff. That’s enough to keep your portfolio afloat, and then some…

Remember: Crowds can be (and often are) wrong… so do your own homework… own some hedges… and don’t be afraid to be a contrarian when you don’t agree with the crowd.

P.S. In today’s volatile market, you NEED hedges against pullbacks…

My Moneyflow Trader strategy consistently turns down markets into triple-digit gains…

And I walk you through it every step of the way.